LAN Data Link Layer Addressing

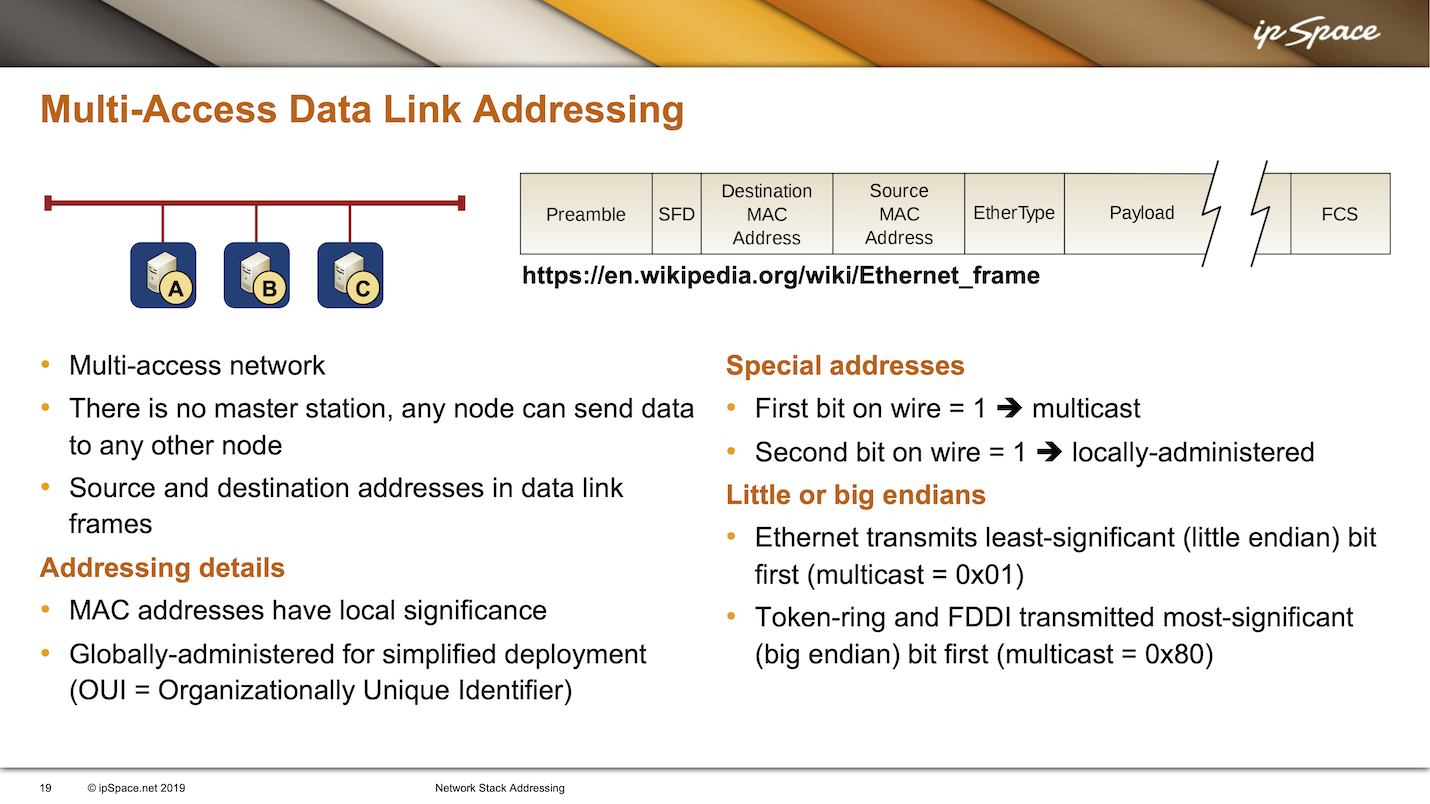

Last week, we discussed Fibre Channel addressing. This time, we’ll focus on data link layer technologies used in multi-access networks: Ethernet, Token Ring, FDDI, and other local area- or Wi-Fi technologies.

The first local area networks (LANs) ran on a physical multi-access medium. The first one (original Ethernet) started as a thick coaxial cable1 that you had to drill into to connect a transceiver to the cable core.

Later versions of Ethernet used thinner cables with connectors that you put together to build whole network segments out of pieces of cable. However, even in that case, we were dealing with a single multi-access physical network – disconnecting a cable would bring down the whole network.

There was a significant difference between these networks and earlier multi-access technologies: LANs had no master station. Their designers wanted to build a peer-to-peer network where any node could send data to any other node, meaning they needed an in-network addressing mechanism2. While one could use addresses from a higher-level protocol (like Fibre Channel does), local area networks had to support over a dozen network layer protocols in those days, each with a different addressing scheme. To be independent of the higher-layer protocols, Ethernet designers decided to add addresses to the data-link layer frames, and that’s how we got destination- and source MAC3 addresses in the Ethernet frames.

Assigning MAC Addresses

MAC addresses should have local significance and should never be seen outside a LAN segment4. Some implementations took that literally and went as far as requiring you to configure MAC addresses manually. In Ethernet, they had a better idea from day one: while the addresses might have local significance, they should be globally administered to simplify deployment. They split the MAC addresses in the middle, with the top part being Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI) and the bottom part being whatever the vendor wants it to be – the top 24 bits of an Ethernet MAC address identify the organization making the Ethernet hardware5. When you look at Ethernet traffic with a tool like Wireshark, the tool can tell you, “This frame is coming from an Intel NIC, that one is coming from a Cisco NIC, and the third one is from an Arista NIC” because all of those manufacturers went to IEEE, got their own OUI, and then (in the manufacturing process) assigned unique IDs to individual interface cards6.

Interesting side story: some manufacturers were too lazy for that. They didn’t want to pay the OUI assignment fee, so they put zeroes in the OUI part of the MAC address. I knew someone who got those interface cards, and when they started complaining to the manufacturer, the manufacturer said, “We get it that you don’t like all zeros in there, so just tell us what you would like us to put in there?” Well, that’s not how Ethernet is supposed to be working.

Multicast- and Locally-Administered MAC Addresses

An interesting tidbit: we have multicast and unicast addresses in Ethernet, which differ in the first bit on the wire. If the first bit transmitted by the sending NIC is zero, the frame is unicast. The receiving NIC has to figure out whether the remaining 47 bits match its MAC address7 and keep receiving the frame if they do8. If the first bit on the wire is one, the frame is a multicast or a broadcast frame, so everyone should listen and at least figure out whether they should be interested in the frame.

Another addressing trivia: the second bit on the wire is set to zero for globally administered addresses and one for locally administered addresses. That’s why all DECnet MAC addresses started with AA-9.

Now for the fun question: which bit in the first byte is the first or the second bit on the wire? The first bit on the wire could be the left-hand (the most significant) bit, in which case its value would be 128 (hex value 0x80). On the other hand, if the least significant bit is the first one on the wire, its value would be 1. As is often the case in IT, they couldn’t agree on what to do. For the last 60 years, we had manufacturers that thought that the most significant bits should come first (big endians, starting with IBM and including manufacturers like Motorola), while other manufacturers believed that the least significant bit (or byte in a multibyte number) should come first. Two of these so-called little endians were Intel and Digital, the I and the D in the original DIX Ethernet (the third one was Xerox)10.

So, on Ethernet, the least significant bit is transmitted first, and multicast addresses always have one in the first byte – they’re always odd numbers. On Token Ring (which was created by IBM) and on FDDI, the most significant bit is transmitted first, which is why you would see multicast addresses in Token Ring or FDDI (if you ever managed to see one of those), starting with 0x80. Likewise, the locally administered bit would have a value of 0x02 in Ethernet and 0x40 in Token Ring or FDDI. And now you know why most Token Ring addresses for IBM mainframes started with 0x4000 – probably one of the most useless bits of information to learn in 2023.

Next: Can We Skip the Network Layer? Continue

-

The coaxial cable had to be bright yellow, and it seems to be indestructible. Someone even managed to revive and use 10BASE5 transceivers in 2012. ↩︎

-

Remember that you don’t need addresses on a point-to-point link. ↩︎

-

MAC stands for Media Access Control – a protocol or agreement allowing you to access the shared media and transmit data. ↩︎

-

We’ll not go into how we stretch Ethernet segments with all sorts of crazy solutions, from bridges and long-distance bridging to bridging over IP with VXLAN or Geneve. ↩︎

-

Or a virtual network interface card – that’s why VMware uses officially assigned OUI (

00:50:56) for virtual machines running on ESXi hypervisors. ↩︎ -

These days, most networking vendors assign a range of MAC addresses to a multi-interface box like a router or a switch. The box then gives MAC addresses from that range to individual interfaces during the power-up process. ↩︎

-

Sometimes called Burnt-In Address (BIA) because, in the ancient days, they used write-once memory modules in which you programmed the contents of the memory by burning the connections. ↩︎

-

The number of unique MAC addresses recognized by a network interface card is limited. Most modern virtualization solutions put the NICs in promiscuous mode – the interface card receives everything, and the software decides whether a frame is worth processing. ↩︎

-

More history trivia: DEC registered locally-administered OUI

AA-00-04with IEEE. ↩︎ -

Another fun fact: Ethernet is little endian while IP is big endian. ↩︎