In September 2020, I created the Switching, Routing, and Bridging Terminology video as part of the How Networks Really Work webinar. This blog post is a Whisper transcript edited/summarized by ChatGPT and polished by Yours Truly ;)

While I’m positive ChatGPT did a great job structuring the transcript and removing my verbal meandering, I wonder how far we got down the slippery slope toward AI slop. Your comments are highly appreciated. Thank you!

Switching, Routing, and Bridging Terminology

After discussing networking layers and addressing, it’s time to focus on moving packets across a network. Vendors love to use ill-defined terms like switching instead of forwarding, routing, or bridging, so let’s start with the terminology.

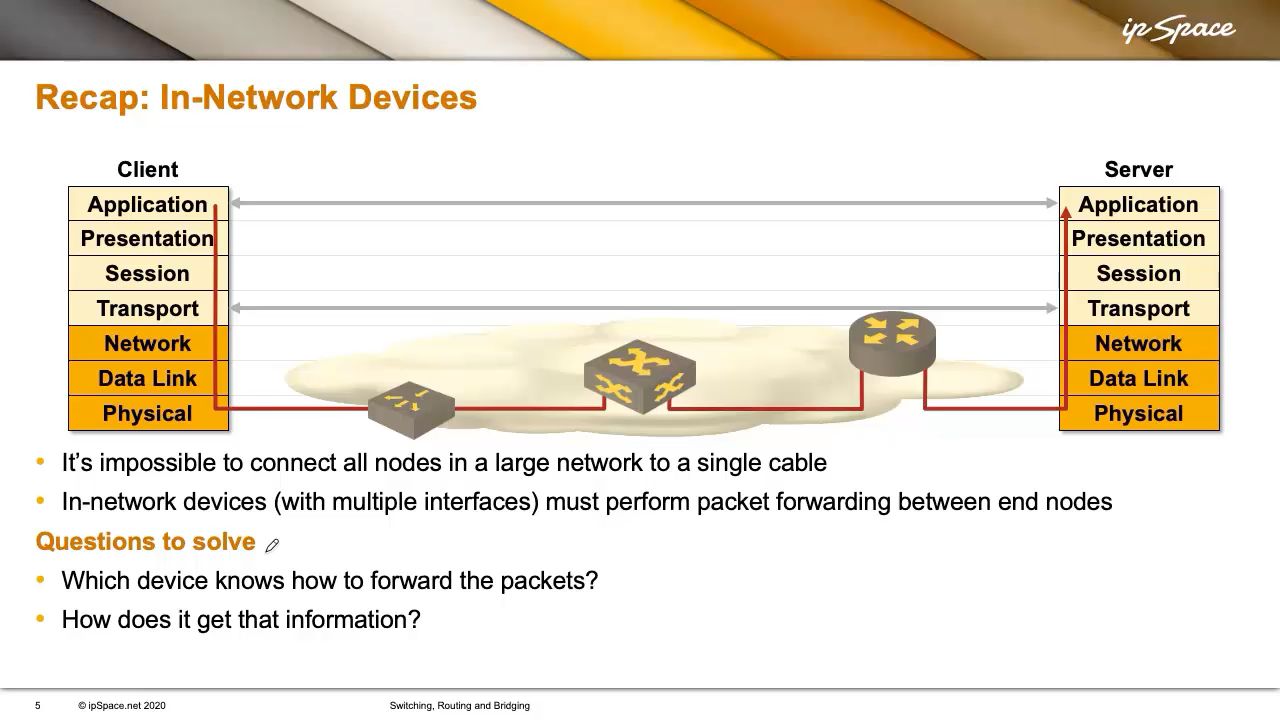

Connecting all relevant devices to a single cable would indubitably simplify any networking stack, but unfortunately, we’re almost never that lucky. We need devices in the network (typically with multiple interfaces) that perform packet forwarding between end nodes.

When we discussed networking layers, I mentioned devices like hubs, repeaters, or media converters. These simply convert bits between different physical media, like copper and fiber.

Next, we have devices that arguably shouldn’t exist: bridges. They connect end nodes at the data link layer. But remember, the data link layer is meant to connect adjacent nodes. Once you insert a bridge, the nodes are no longer adjacent.

Finally, we have routers – Layer 3 devices that operate at the network layer. Theoretically, any large network (your home Wi-Fi, a corporate LAN, or the global Internet) should use routers to interconnect segments.

Now that we know which devices can perform packet forwarding, let’s focus on two big questions:

-

Which device knows how to forward the packet?

If you’ve worked with IP, your instinct might be: “The router does!” But that’s only one forwarding paradigm. Sometimes, the sender determines the forwarding path—by selecting a virtual circuit, for instance—and devices in the network only recognize those circuits. We’ll examine at least three forwarding paradigms and identify which technologies, past and present, use each.

For example, segment routing isn’t that different from source-route bridging in Token Ring. Nothing is truly new in networking—we’ve just reinvented ideas over time.

-

How does a device know how to forward a packet?

Regardless of whether a device is an end node or an in-network device, it needs to get that information from somewhere. It might guess, get it from a central controller, or learn it from adjacent or non-adjacent devices.

The Three Planes of a Networking Device

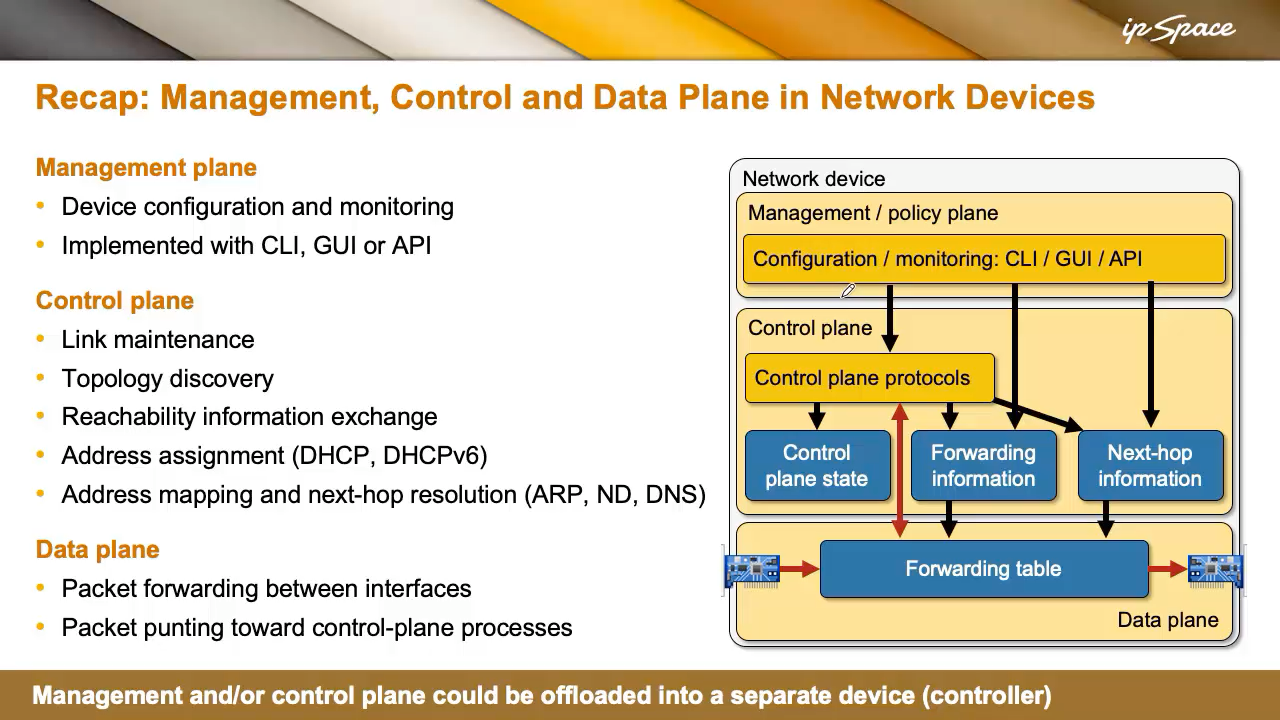

In any device that performs packet forwarding, there are three key planes:

-

Data Plane: This is where the actual forwarding happens. The device uses a forwarding table to determine how to send a packet, based on information like MAC addresses, IP addresses, MPLS labels, etc.

If the data plane can’t handle the packet—perhaps it’s too complex or destined for the device itself—it’s punted to the control plane.

-

Control Plane consists of processes running in the device’s OS (often Linux or another Unix-based system). These processes handle tasks like:

- Link Maintenance (e.g., using BFD)

- Topology Discovery (handled by routing protocols like OSPF or IS-IS)

- Address Assignment (e.g., DHCP, SLAAC)

- Address Mapping (e.g., ARP for IPv4, Neighbor Discovery for IPv6)

-

Management Plane handles configuration and monitoring. In the old days, we used console cables to configure devices. Today, many devices boot from the network and are managed via SSH, Telnet, or APIs.

A decent device should support at least a CLI and an API, so it can be managed manually or via automation tools.

Routing Protocols and the Forwarding Table

Routing protocols—like OSPF, IS-IS, or BGP—run in the control plane. They:

- Build internal topology or route databases.

- Calculate routing tables.

- Combine routing information with data link layer mappings to create the forwarding table.

This forwarding table is what the data plane uses to efficiently forward packets.

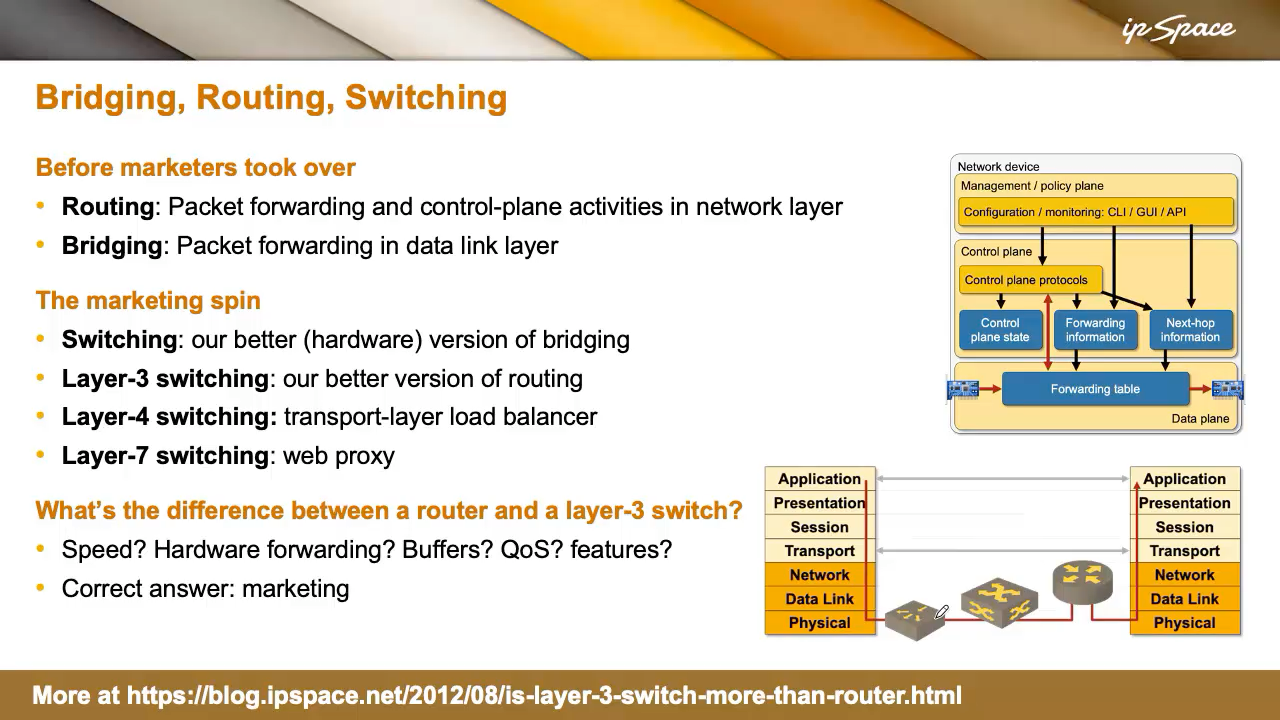

Layer-2 vs Layer-3 Forwarding (And Marketing Confusion)

There are two major ways to forward packets across a network:

- Layer-2 forwarding (Bridging) is based on the data-link layer (MAC) addresses. It’s simple to implement in hardware.

- Layer-3 forwarding (Routing) is based on the network layer (IP) addresses. It requires more complex packet header parsing and prefix-based lookups in the forwarding table.

- Some devices, like load balancers or firewalls, use flow-based packet forwarding.

Early bridges did layer-2 forwarding in software and barely managed to deal with two 10 Mbps Ethernet ports. When vendors began implementing bridging in hardware, they coined the term switching to differentiate between hardware- and software-based bridges. Later, when Layer 3 forwarding became fast enough in hardware, we got Layer 3 switching. It was all marketing—designed to position products against larger competitors like Cisco.

In reality, what’s the difference between a router and a Layer 3 switch? Just marketing. Performance, buffers, or features don’t define it. The label depends on what the vendor wants to call the device.

Terminology Clarification

In this webinar, I’ll try to use consistent terminology:

- Switching = any packet forwarding.

- Layer 2 Switching = forwarding based on MAC addresses.

- Bridging = usually refers to transparent Ethernet bridging.

- Layer 3 Switching = forwarding based on IP addresses (IPv4 or IPv6).

- Routing = path selection and control plane activities related to IP forwarding.

Q&A Highlights

Q: Are there any control plane activities at Layer 2?

A: Almost none. Transparent bridges don’t run control plane protocols between themselves and end nodes. They rely on dynamic MAC learning in the data plane. Protocols like STP provide basic loop prevention but offer minimal discovery or routing.

Q: Isn’t all switching capable of routing today?

A: Not always. High-end data center switches often support full IP routing. But in campus or industrial environments, you’ll still find switches that need separate licenses for routing or only support bridging.

It's so refreshing to hear someone call switching a marketing term. I'm surrounded by people who don't know the actual difference between switching and bridging. I know at least one person who defines firewalls as a layer 3 device and IP forwarding in switches as a layer 2+ function. It isn't layer 3 unless the device has packet filtering apparently...even though that often uses layer 4 information. sigh