Addresses in a Networking Stack

After discussing names, addresses and routes, it’s time for the next question: what kinds of addresses do we need to make things work?

End-users (clients) are usually interested in a single thing: they want to reach the service they want to use. They don’t care about nodes, links, or anything else.

End-users might want to use friendly service names, but we already know we need addresses to make things work. We need application level service identifiers – something that identifies the services that the clients want to reach.

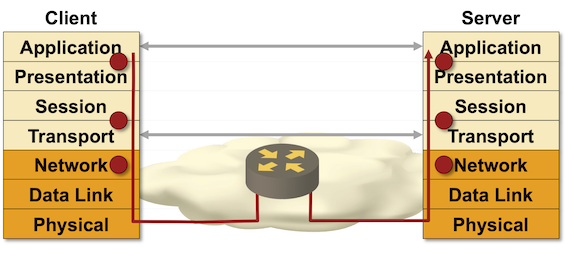

To reach that service, the client’s node has to establish connections with the servers offering the service, so we need some sort of connection identifier – something that identifies the virtual link between the client and the server. These virtual links are always established between two or more endpoints1, so we need some endpoint identifiers.

Everything else is optional. Do we need data-link addresses? Maybe we do, maybe we don’t. There is no need for data-link addresses on a point-to-point link. Do we need network addresses? Most probably we do, unless our “network” has just two isolated nodes2, in which case even the network addresses are optional.

Interestingly, even though we might not need data-link or network-layer addresses, we always need service identifiers3. Even if you are working on an isolated laptop with no internet connectivity and all you have is the loopback address, you still need TCP port 80 associated with a web server and TCP port 22 associated with a SSH server.

Now all this might seem a little bit academic, so let’s figure out how these concepts map into the TCP/IP stack.

You might think that the DNS names would be good application service identifiers. Turns out that DNS names are not a good example because they identify nodes not services. You still need the secret sauce called the TCP (or UDP) port number – for example, you have to know that a web server is sitting on port 80 or 443. That works pretty well, unless (for whatever reason) the web server is sitting on port 8080.

It’s interesting that DNS supports SRV records that you can use to say “my web server is sitting on TCP service on this host and this port number.” For whatever reason, they are rarely used.

Next: the connection identifiers. In the TCP/IP world one might think that the TCP or UDP port numbers would be what we’re looking for, but they address the endpoints, not connections. You might say “my web server is reachable on port 80” but that does not tell you how to send requests to it – it’s and endpoint, not a connection. After establishing a connection to this web server, we still need a connection identifier to send requests to it.

Interestingly, there is no connection identifier in the TCP/IP world. We use a hack and pretend the source IP address, the destination IP address, the source port, the destination port, and the transport protocol (usually TCP or UDP) uniquely identify a connection.

Going down to the network layer, we have to identify the network elements. In TCP/IP world, we do that by using IP addresses, which identify interfaces, not nodes4. And finally, on the data link layer, we have to identify the interface card in the machine – that would be Ethernet MAC address or Wi-Fi MAC address.

Next: Early Data-Link Layer Addressing Continue

-

More than two in case we’re talking about one-to-many communication, for example real-time streaming over IP multicast. ↩︎

-

Fellow GONERs might remember transferring files between two computers with Kermit or ZMODEM. ↩︎

-

Unless your networking stack supports a single single service, in which case even service identifiers are optional. ↩︎

-

We’ll get into that distinction when we start comparing TCP/IP and OSI protocol stacks. ↩︎