Running BGP between Virtual Machines and Data Center Fabric

Got this question from one of my readers:

When adopting the BGP on the VM model (say, a Kubernetes worker node on top of vSphere or KVM or Openstack), how do you deal with VM migration to another host (same data center, of course) for maintenance purposes? Do you keep peering with the old ToR even after the migration, or do you use some BGP trickery to allow the VM to peer with whatever ToR it’s closest to?

Short answer: you don’t.

Kubernetes was designed in a way that made worker nodes expendable. The Kubernetes cluster (and all properly designed applications) should recover automatically after a worker node restart. From the purely academic perspective, there’s no reason to migrate VMs running Kubernetes.

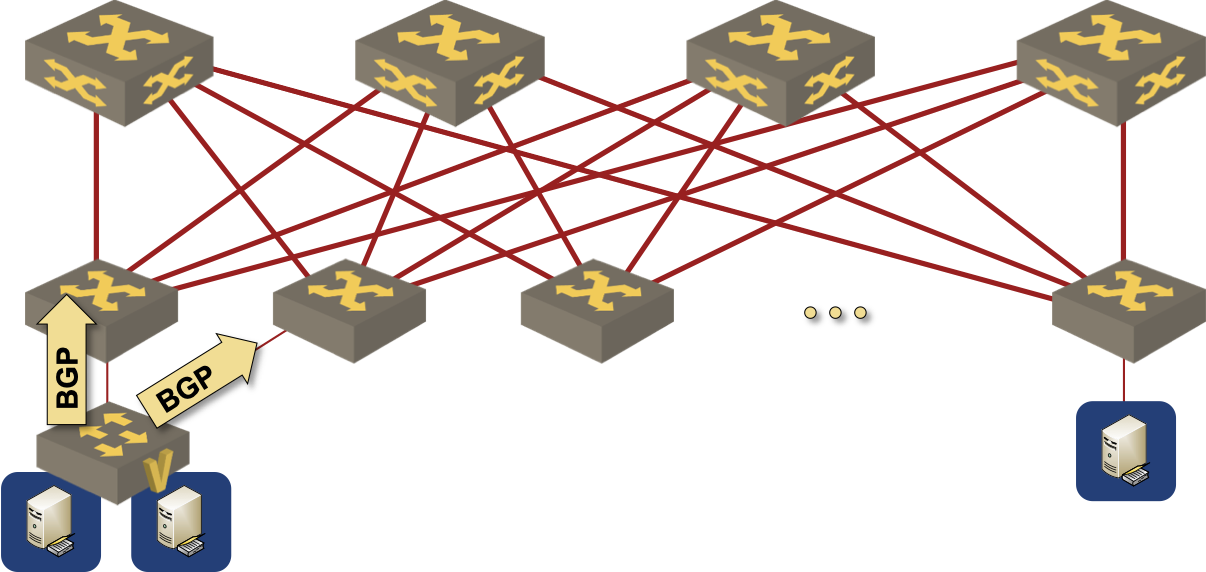

A virtual switch in a Kubernetes node advertising a BGP prefix to the data center fabric

Meanwhile on Planet Enterprise: all sort of **** is being deployed in containerized format. A lot of those things were never designed, let alone designed properly, and the application developers are still too often able to get away with murder and blame the infrastructure teams when their non-redundant application stack dies (for whatever reason, that approach does not work in public clouds).

Even though it hurts me to do so, let’s walk through the realistic options, starting with the bad ones and ending with the abhorrent ones.

Deploy Kubernetes clusters connected to a single ToR switch pair. If you’re working in an enterprise environment, you probably use dual-connected physical servers, and there’s high probability that the failover between server uplinks is done on layer-2 (more details). It’s thus realistic to expect a set of VLANs stretching across the ToR switch pair:

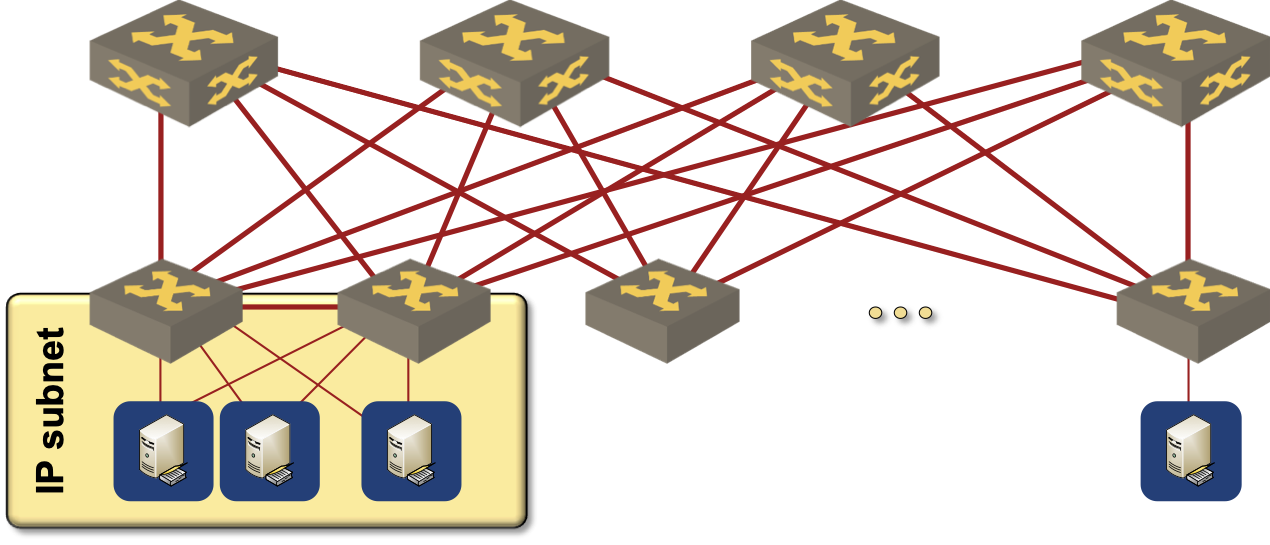

A VLAN (and an IP subnet) is spanning a pair of ToR switches

Assuming you managed to keep the VM mobility domain within the ToR switch pair, here’s how you can design BGP routing:

- EBGP sessions are established from the outside interface of the virtual machine to the directly-connected IP address of the first-hop ToR switches (the actual switch IP address, not the anycast gateway).

- ToR switches redistribute EBGP routes into the data center fabric.

- Whenever a VM moves, it stays connected to the same VLAN and adjacent to the same set of ToR switches.

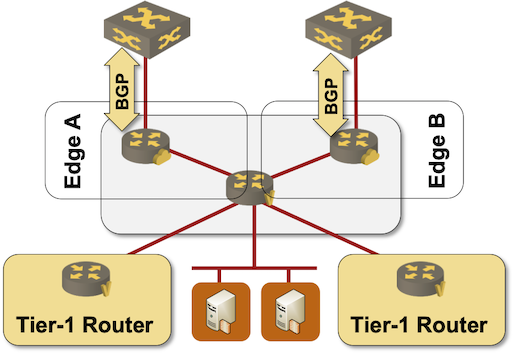

Not surprisingly, this is how NSX-T Edge nodes are supposed to be deployed (more details).

Deploying NSX-T Edge node

The obvious drawback: both ToR switches will attract the inbound traffic for all containers deployed in the cluster. The peer link will have to carry tons of traffic. You might want to solve that challenge with MLAG, but I don’t want to hear how convoluted that gets and what bugs software features you might hit trying to get it done.

Next step: the application developers want to have more redundancy. The correct implementation of that requirement would be a set of Kubernetes clusters (making sure there’s no single point of failure) and an application designed with well-separated swimlanes (more details). Fat chance; in most cases the networking team gets yet another curveball.

Now we’re entering the abhorrent territory. If you want to migrate VMs across the whole data center, then they shouldn’t have BGP sessions with adjacent switches (the proof is left as an exercise for the reader). You should peer the VMs with a stable point somewhere deep inside the data center fabric – the fabric route reflectors, regardless of whether they are implemented on spine switches or on dedicated virtual machines:

- Establish multihop EBGP sessions from the outside interface of the virtual machine to the loopback interface1 of the route reflector

- The next hop of the prefixes advertised by the virtual machines is reachable within the data center fabric – when the route reflector(s) advertise the routes received from the virtual machines to other routers in the fabric, everyone knows where to send the traffic.

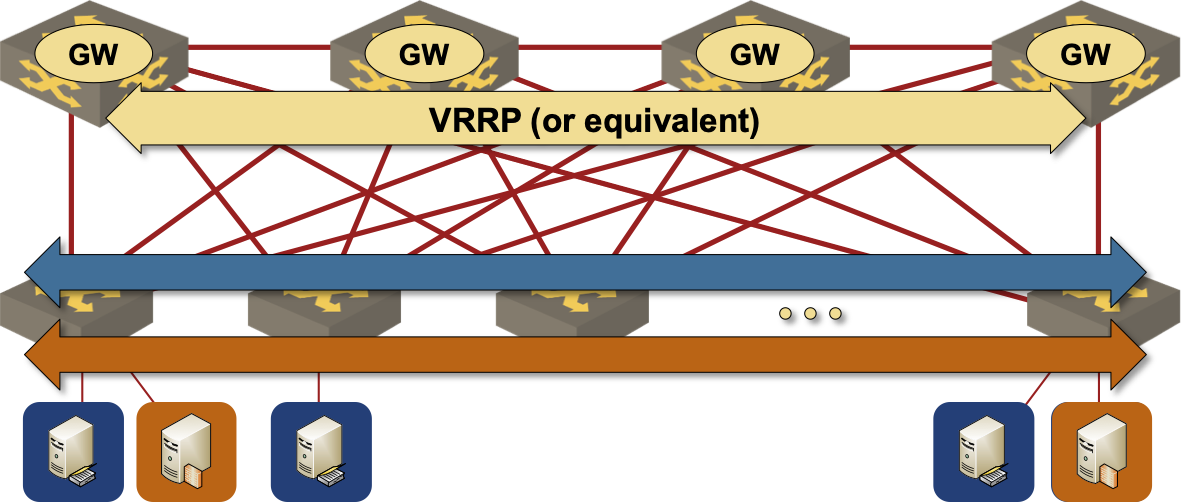

If you’re running a traditional layer-2 fabric with centralized routing on the spine switches (more details) you’re done.

VLANs are spanning the whole fabric, inter-VLAN routing is performed on spine switches

If you happen to be running EVPN, there’s just a tiny little gotcha (pointed out by Nicola Modena): the EBGP sessions with the virtual machines have to be established within a VRF, and the routes received from the virtual machines have to be advertised into EVPN address family as Type-5 (IP prefix) routes. Here’s what he sent me:

The result it’s a 2 step lookup:

- BGP advertisement of POD and Service addresses with the Worker IP address as next-hop. The worker IP address is resolved to an IP address in the VXLAN network.

- L2 EVPN lookup to resolve BGP next-hop through EVPN type-2 advertisement

The efficiency of the lookup depends on what EVPN routes are advertised into the fabric and which node advertises them.

There is an optimization that Juniper calls VMTO (virtual machine traffic optimization): redistribute the connected VM IP (as learned via ARP) as EVPN type-5 route into the EVPN fabric. Cisco performs this by default in recent NXOS releases and (advertise-pip must be configured if you are also using VPC).

The ingress leaf can then resolve:

- BGP advertisement of POD and Device addresses into Worker IP address as the BGP next-hop

- BGP next-hop is resolved directly to a pure EVPN type-5 VM address pointing to the VTEP of the leaf that is currently directly connected to the corresponding MAC address.

The end result: you get redundant BGP sessions and an always-optimal path regardless of VM movements or BGP peering location.

He concluded with an interesting caveat:

… but we are sinking into an extremely dangerous field, where we have multiple levels of BGP next-hop recursion. You could get surprising results, especially in EVPN fabrics that use EBGP as the underlay routing protocol.

The details are left as an exercise for the reader. Alternatively, Nicola is also available for on-site or online consulting projects.

More Details

You might find these webinars interesting:

- If you’re trying to solve a Kubernetes network challenge, you MUST start with Kubernetes Networking Deep Dive

- Leaf-and-Spine Fabric Architectures discusses the intricate details of routing and switching designs in data center fabrics.

- I mentioned VMware NSX-T; the relevant technical details are in VMware NSX Technical Deep Dive

- Finally, no blog post talking about data center fabric design would be complete without a mention of fantastic EVPN Technical Deep Dive webinar.

-

Or the outside interface of a BGP route reflector running in a virtual machine. ↩︎

What about some load balancer instances (e.g. MetalLB) in front of Kubernetes cluster doing EBGP (host routes + ECMP) with ToR switches? Combined with global load balancing (DNS). Let Kubernetes cluster handle movement of Pods (containers). No need for moving around Nodes in the data center.

Glad to see someone agrees with me ;) Thank you!

Few points In Junos the solution is not VMTO but to advertise type-2 routes as /32 type-5 (It simulate symmetrical IRB on Junos ) and add the following command to allow the next-hop resolution.

set routing-options resolution preserve-nexthop-hierarchy(Use recent Junos for it )The same solution works also in Arista without special knobs.

If you want to do anycast for some services you should add add-path to the mix.

There is more elegant solution for the issue by establishing the BGP to centralized leaf (two for redundancy) in the network regardless of its location. that leaf will advertise the route as type-5 to all of the other leafs but it will set the GW IP attribute to the K8S worker IP (It is 0 by default). This way the ingress leaf will not forward the traffic via the centralized leaf that advertise the type-5 but it will use the optimal path do the K8S worker. AFAIK only cisco support it today via

set evpn gateway-ip use-nexthopunder route-map as you can read here https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/td/docs/dcn/whitepapers/cisco-nx-os-calico-network-design.html. More details are in rfc9135 and rfc9136