… updated on Tuesday, August 13, 2024 07:26 +0200

Back to Basics: The History of IP Interface Addresses

In the previous blog post in this series, we figured out that you might not need link-layer addresses on point-to-point links. We also started exploring whether you need network-layer addresses on individual interfaces but didn’t get very far. We’ll fix that today and discover the secrets behind IP address-per-interface design.

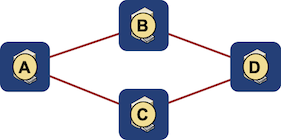

In the early days of computer networking, there were three common addressing paradigms:

- Companies building large-scale networks connecting mainframes or minicomputers (IBM and DEC) realized you need a unique network-wide identifier per node, not per interface. After all, you want to connect to the services running on a node, and nobody (apart from the network administrator) cares about individual node interfaces.

Assign network addresses to nodes, not links

- Companies building LAN-based client-server networks (AppleTalk, Novell Netware…)1 didn’t care about the distinction between node- and interface addresses. The devices connected to their networks had at most one interface anyway.2

Keep things simple: assign network addresses to interfaces

- Anything mentally based on the phone network paradigm assigned addresses to switch ports, and the nodes attached to the network had to use the address of the connected switch port, or they wouldn’t receive any traffic. You could say that the switches used static host routing, with a host route pointing to every edge port.

Where does IP fit into this picture, and how did we get to interface addresses where it would be much better for IP routers and multihomed hosts to use node addresses?

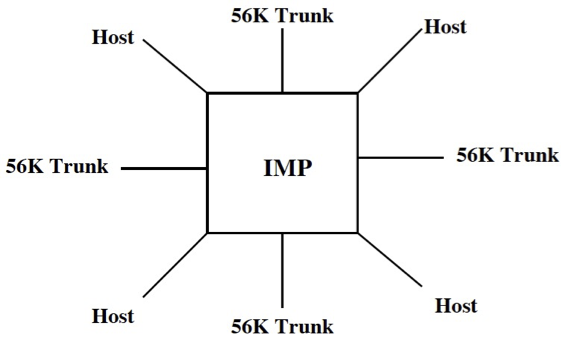

You have to remember that IP didn’t start as a network protocol. IP stood for Internetworking Protocol and was designed by a bunch of academics trying to make sense of an underlying network built by BBN (see BBN Report 1822 for the details). IP addresses were statically assigned to the ports of the Interface Message Processor, with part of the original IP address being the IMP identifier and the second part being the port number on the IMP3.

An IMP in a nutshell

Deciding to use interface-scoped network addresses when designing a protocol to fit that environment was an obvious choice. After all, if a host connected to two IMP ports, it had to use two IP addresses, and who would want to burn two IMP ports anyway?

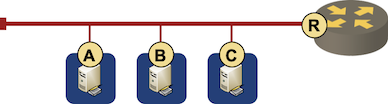

Eventually, IP networks were extended to Ethernet segments. The gateways between the original BBN network and the LAN network had to use two IP addresses - one for the BBN part and another for the LAN part. When subnets were introduced to split LAN networks into smaller routable bits, the architecture was already cast in stone.

Let’s use per-link prefixes to make our lives simpler

IPv6 was another missed opportunity. The difference between node-level and interface-level network addresses was well understood then. DEC’s experience building large-scale WAN and LAN networks influenced the OSI CLNP protocol design; CLNP consequently used node-level addresses. There were even ideas to use CLNP as the basis for next-generation IP. Still, following a grassroots revolt4, IAB decided to start from scratch. The “we always did things this way” mentality quickly kicked in together with a copious amount of Second System Effect.

Does that mean using a CLNP-like design with node-level network addresses would be better? Not necessarily:

- Node-level network addresses are harder to summarize. In IP networks, routers must know about subnets and directly connected nodes. In CLNP networks, routers must know about all nodes in an area.

- Regardless of what some academics claim, node-level addresses wouldn’t solve the multihoming problem. They would get rid of the loopback interface hack and resolve the local multihoming issue (node connected to the network with two or more interfaces) for good… but it’s impossible to solve the challenge of nodes connected to multiple networks (example: WiFi and LTE, or two upstream ISPs) without a proper session-layer protocol.

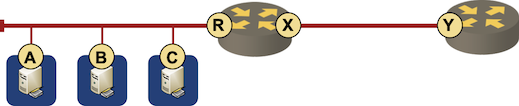

Slightly off-topic: It still doesn’t make sense to be forced to use an IP subnet for every point-to-point router-to-router5 link. Welcome to the mysterious world of unnumbered IP interfaces.

Solving Local IP Multihoming with Loopback Interfaces

Before it became fashionable to solve every networking problem with a layer-2 hack, we used loopback interfaces on mission-critical servers that had to be available even after a link/subnet failure:

- A global IP address was configured on a loopback interface6.

- The server was running a routing protocol (usually RIP or OSPF) with the adjacent routers and advertising the loopback IP address.

- The clients connected to the loopback IP address, and thus, the TCP sessions survived network errors as long as at least one path to the server was operational.

You’ll find more details in:

- Redundant Layer-3-Only Data Center Fabrics

- Running BGP on Servers

- Why Would I Use BGP and not OSPF between Servers and the Network?

- Virtual Appliance Routing – Network Engineer’s Survival Guide

Next: Back to Basics: Unnumbered IPv4 Interfaces Continue

More to Explore

Why don’t you watch the Network Addressing part of How Networks Really Work webinar to get even more details?

Revision History

- 2024-08-13

- Described the loopback interface hack

-

Lovingly called desktop protocols by Cisco TAC. ↩︎

-

Netware servers were an exception, but Novell engineers realized that too late and had to settle for the same loopback interface hack we use in IP networks today. ↩︎

-

SAN geeks might realize Fibre Channel still uses the same approach. ↩︎

-

You might find a few hints about that event in the hilarious Elements of Networking Style book. ↩︎

-

People believing in vague marketese are free to replace that with a switch-to-switch link. ↩︎

-

You had to create an additional loopback interface if the operating system did not support multiple IP addresses per interface. ↩︎

In your "was CLNP really broken" post you state that host-based adressing doesn't scale. Could you explain why that is the case?

With host-based addressing, the routers have to advertise individual host addresses in routing protocols (at least until the first summarization boundary). With subnet-based addressing, they only advertise subnets.

Not that we couldn't solve that today (after all, we're often using host routing in IP), but 30 years ago it was a big deal.