Comparing IP and CLNP: Local (Node) Multihoming

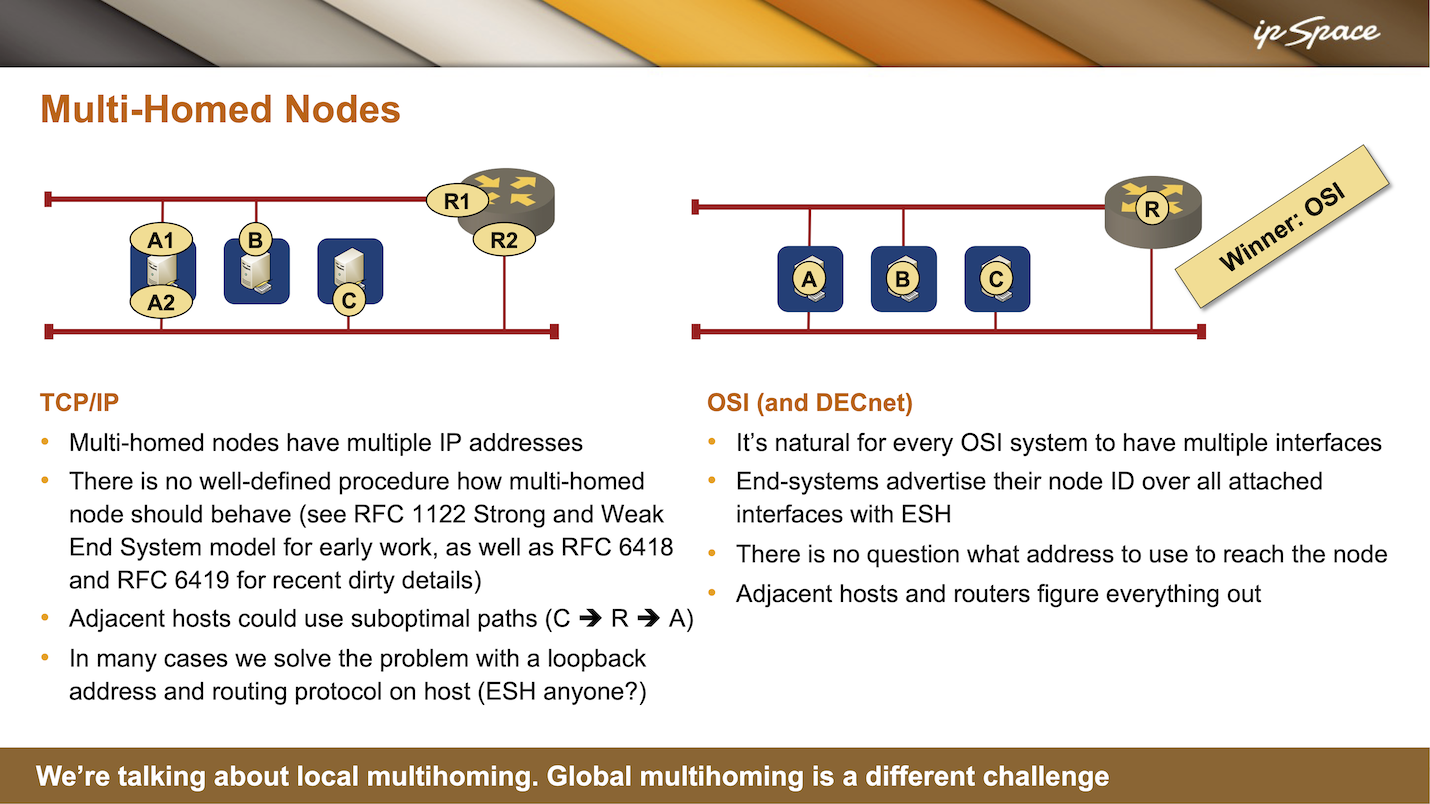

Another area where CLNP is a clear winner when compared to the TCP/IP stack is multi-homed nodes (nodes with multiple interfaces, not site multi-homing, where whole networks are connected to two upstream providers).

Multi-homed TCP/IP nodes must have multiple IP addresses because IP uses address interfaces. There is no well-defined procedure in TCP/IP for how a multi-homed node should behave. In the early days of TCP/IP, they tried to address that in RFC 1122 (Host Requirements RFC), but even then, there were two ideas about dealing with multiple interfaces: the strong and weak end system models (more details).

Assume that someone is sending traffic to A2 (one of the IP addresses on host A). Should the outgoing traffic only be sent through this interface (the strong end-system model)? Or, if the host has a default route pointing to R1, can the traffic be sent that way (the weak end-system model)? Most TCP/IP implementations today use the weak end-system model, making it hard for multi-homed hosts or servers to work correctly. Traffic might come in on one interface and be sent out through another.

For example, one of my customers used an IBM mainframe in such a setup. They wanted to place a firewall in front of it for obvious reasons, but they couldn’t use stateful firewalling because the mainframe always sent return traffic the wrong way.

Even worse, a multi-homed host might use sub-optimal paths, sending traffic through the router even when it could reach the desired destination directly.

The solution in TCP/IP is to assign a third IP address (the loopback address) to the host and use a routing protocol to advertise this loopback address to the router. Adjacent routers would know how to get to the host, which makes the host routing protocol updates look almost like the end-system hello in OSI.

Interestingly, the routers could also send a packet to the host in multiple ways. Assume that A advertises its loopback interface (let’s call it AL) and B sends a packet to AL. B does not know where AL is and sends the packet to the router (R1). However, the router might forward the packet toward A1 and send an ICMP redirect packet to B, telling it to communicate directly with A1. After receiving the ICMP redirect, B would install a host- or prefix route pointing to a different next hop and use that for further IP datagrams.

ICMP redirects are often turned off because they can be exploited as a denial-of-service vector. Nasty actors could send misdirected packets to the router, which would keep sending ICMP redirects, overloading its CPU.

Alternatively, an intruder could send ICMP redirects to the end host, and the host would start using that information, sending traffic to someone else. For example, if C and B are connected to the same subnet and C is talking to A, B could send an ICMP redirect to C, saying, “Send whatever you want to A to me.” C, being polite, would start sending traffic for A to B, who could inspect, modify, or do whatever with the traffic before sending it to A.

See ICMP Redirects and Suboptimal Routing and ICMP Redirects Considered Harmful for more details.

In the CLNP world, life is easy. Every system could have multiple interfaces and a single NSAP (CLNP address) because CLNP uses node (not interface) addresses. There’s never a question of how to reach the node; you can use any interface through which it is sending end-system hellos. The adjacent hosts and routers figure everything out.

To achieve the same results in the IP world, every server must have loopback interfaces and advertise them using a routing protocol (RIP in the old days, BGP in modern data center fabrics). All other routers and servers would participate in the same routing protocol and install host routes as needed, turning a TCP/IP network into a poor man’s equivalent of a CLNP network.

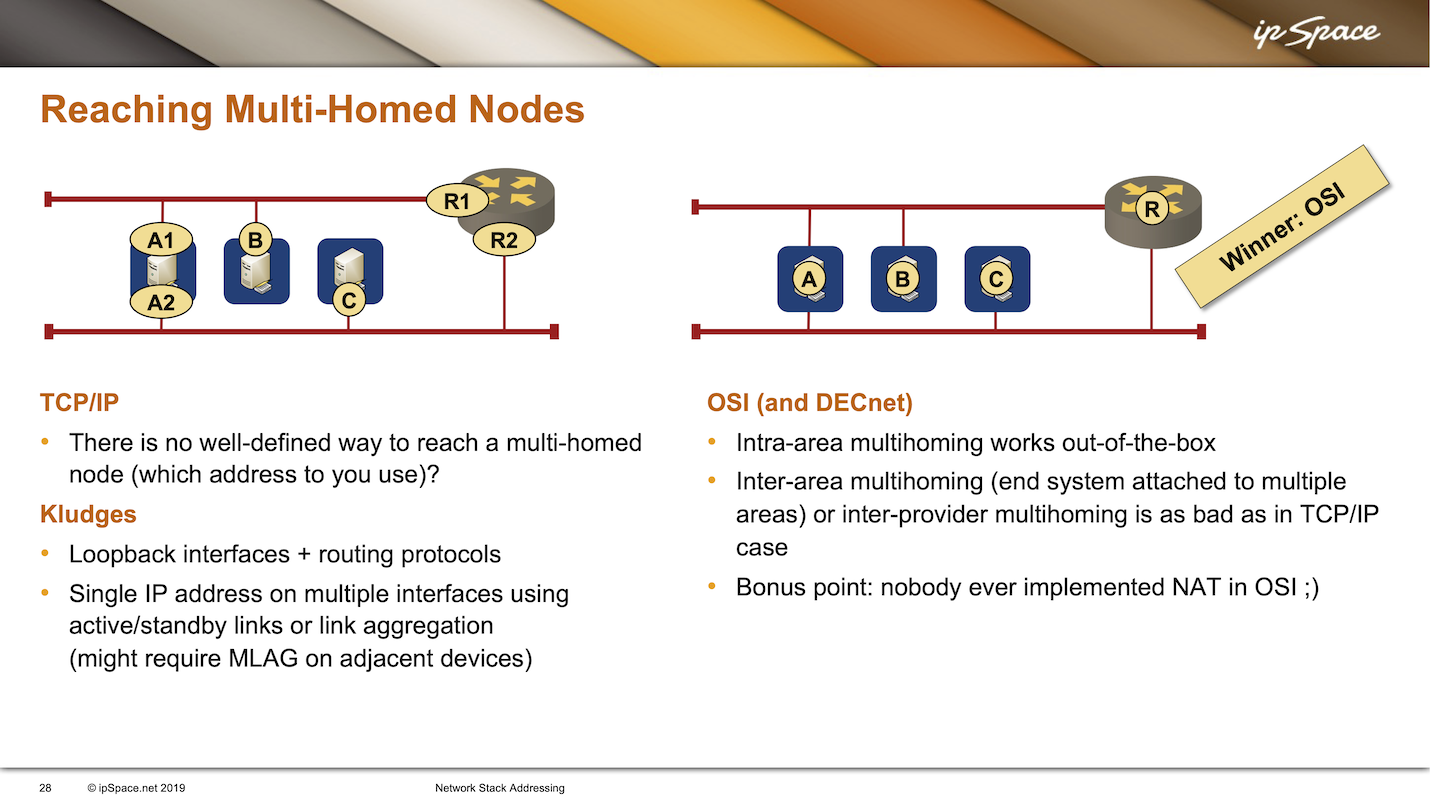

Ignoring the outgoing traffic issues for the moment, let’s try to figure out how the clients reach multi-homed servers. In some scenarios (primarily storage networks), clients have multiple addresses attached to the same segments as the servers, use directly connected server IP addresses, and deal with failures on the application layer (more details).

That approach does not work in more generic scenarios. We commonly use server loopback interfaces with routing protocols, or we pretend a server has only one IP address by bundling two uplinks into one Layer 2 link with link aggregation (we could also use DNS, which opens a whole new can of worms). Alternatively, we might give up and use only one of the available uplinks, resulting in the active/standby links commonly used on Linux hosts.

In CLNP, the node multihoming works out of the box because an end system can be attached to multiple interfaces; the adjacent routers detect this through end-system hellos. You could go even further by having a host attached to more than one area. Such a host could reach directly connected hosts in all areas and use one of the adjacent routers to reach other destinations.

Unfortunately, neither TCP/IP nor CLNP have a good solution for site-level multihoming. One could solve that problem on the session layer (which is missing in TCP/IP) or in the application. However, even though we have been aware of the problem for decades, we still don’t have a good generic multi-homing solution.

As a plus benefit, you get a true multilink mobility support without any additional stuff. Even PMIPv6 cannot do that kind of mobility, since it is only good for single link mobility.

And then you can combine mutlink mobility with site multihoming. Perfect solution for safety critical and mission critical networks.