Point-to-Point Links in Virtual Labs

In the previous blog post, I described the usual mechanisms used to connect virtual machines or containers in a virtual lab, and the drawbacks of using Linux bridges to connect virtual network devices.

In this blog post, we’ll see how KVM/QEMU/libvirt/Vagrant use UDP tunnels to connect virtual machines, and how containerlab creates point-to-point vEth links between Linux containers.

QEMU UDP Tunnels

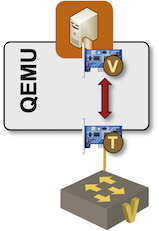

I already mentioned that QEMU (the program that does all the real work when you run KVM virtual machines on a Linux server) emulates a virtual NIC for its VM guest and shuffles packets between the input/output queues of the virtual NIC and a Linux tap interface connected to a Linux bridge.

QEMU forwarding packets between VM NIC and Linux tap interface

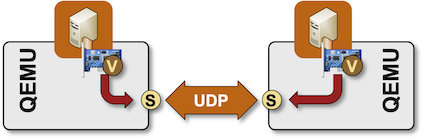

However, exchanging packets between VM NICs and Linux interfaces is not required. QEMU could use any other infrastructure to transport VM packets, including TCP and UDP sockets. It can even use multicast destination addresses on UDP sockets to emulate a multi-access Ethernet subnet1.

QEMU forwarding packets between VM NIC and UDP socket

Figuring out how to get from Vagrant to QEMU UDP tunnels requires a recursive application of RFC Rule 6a:

- Vagrant passes whatever is specified in Vagrantfile network parameter to vagrant-libvirt plugin.

- vagrant-libvirt plugin creates libvirt XML definition for the VM NIC2

- libvirt uses the interface XML definition to create CLI arguments for the qemu command.

- The ultimate source of truth is found in the arcane QEMU invocation document hidden deep in the bowels of the Network Options section.

The Vagrantfile definitions specifying a UDP tunnel between two virtual machines are also a masterpiece of obfuscation:

x1.vm.network :private_network,

:libvirt__tunnel_type => "udp",

:libvirt__tunnel_local_ip => "127.1.1.3",

:libvirt__tunnel_local_port => "10001",

:libvirt__tunnel_ip => "127.1.1.1",

:libvirt__tunnel_port => "10002",

:libvirt__iface_name => "vgif_x1_1",

auto_config: false

...

s1.vm.network :private_network,

:libvirt__tunnel_type => "udp",

:libvirt__tunnel_local_ip => "127.1.1.1",

:libvirt__tunnel_local_port => "10002",

:libvirt__tunnel_ip => "127.1.1.3",

:libvirt__tunnel_port => "10001",

:libvirt__iface_name => "vgif_s1_2",

auto_config: false

Fortunately, we have several tools (including netlab) to create Vagrantfile from a higher-level specification (the original netlab use case).

Finally, it’s worth mentioning an unpleasant quirk of the UDP tunnels. They don’t use Linux interfaces, making it impossible to do simple packet capture on VM-to-VM links. QEMU does provide a traffic capture CLI command3 that saves packets into a file, and there might be a Wireshark plugin out there that strips the UDP header automatically (or you could create custom decoding rules). netlab uses a workaround: it politely tells you how to replace a UDP tunnel with a Linux bridge.

Point-to-Point Container Links

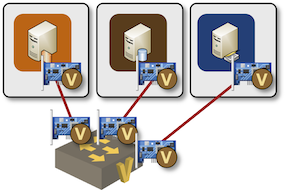

Docker implements container networking with vEth pairs, connecting one end of the virtual cable to a Linux bridge and placing the other end of the cable into a container network namespace.

Containers connected to a Linux bridge

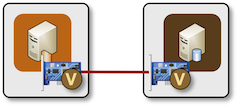

When you ask containerlab to create a point-to-point link between two containers, it bypasses Docker networking, creates the vEth pair, and places the ends of the virtual cable directly into two container network namespaces.

Direct point-to-point link between two containers

That’s a perfect solution from the device connectivity perspective. The containers receive whatever their peer sends them, allowing you to implement whatever networking constructs, including custom STP or MLAG solutions. Even better, the configuration is trivial. This is all you have to specify in a containerlab topology file to create a link between two containers:

links:

- endpoints:

- "s1:eth1"

- "s2:eth1"

There’s just a minor inconvenience: Docker knows nothing about those point-to-point links. If a container crashes, the vEth pair is lost and cannot be recreated when Docker restarts the container. You can recreate the links with the containerlab tools veth create, but it’s cumbersome, and you never know how well network devices respond to suddenly-disappearing interfaces.

Finally, as I mentioned packet capture woes of UDP tunnels: tcpdump works on point-to-point vEth pairs if you start it within the container network namespace with the ip netns exec command. netlab provides a convenient wrapper around that command, and the containerlab packet capture documentation is excellent 4.

Worth the Effort?

Point-to-point UDP tunnels or vEth pairs are a much better option than Linux bridges if you want to build a realistic network in a virtual lab. They transparently pass traffic between network devices, allowing you to test layer-2 control-plane protocols like STP or LACP and evading the stupidities like the default dropping of bridged IPv6 traffic.

Next: Stub Networks in Virtual Labs Continue

-

According to cryptic QEMU documentation. Not tested. ↩︎

-

Libvirt developers further try to confuse you by calling the parameter specifying the destination IP address source and the parameter specifying the source IP address local. ↩︎

-

Good luck enabling it through a half-dozen layers of abstraction ;) ↩︎

-

Roman Dodin knows how necessary good documentation is. One could only wish that other open-source developers would share that mindset. ↩︎