Non-Stop Forwarding (NSF) 101

Non-Stop Forwarding (NSF) is one of those ideas that look great in a slide deck and marketing collaterals, but might turn into a giant can of worms once you try to implement them properly (see also: stackable switches or VMware Fault Tolerance).

The Basics

Long long time ago network devices had a single CPU and used it to run a control plane and perform software-defined networking CPU-based packet switching. There was nothing one could do if such a device crashed, so we all learned the basics of redundant network designs, including “if you want true redundancy, use at least two uplinks connected to two independent boxes”.

It seems to me that the art of good network design got clobbered the moment traditional telcos hooked on big shiny boxes discovered IP routing. They didn’t want to hear about network design or configuration automation, they wanted to have an equivalent of class 5 telephone switch for IP… and so we got redundant fabrics and supervisor modules in large chassis1.

Once you have redundant CPU modules, someone is bound to come up with a great idea: “can’t the second CPU take over at the moment the first one fails”. That would be Stateful Switchover, a topic for a future blog post.

Another idea along the same lines pops up the moment the packet forwarding is offloaded from the control-plane CPU to ASICs or line cards: can’t we keep the packets moving even if the control-plane CPU crashed? After all, the forwarding data structures are intact. That’s how Non-Stop Forwarding started.

Should You Use Non-Stop Forwarding?

Good network design is always better than hidden complexity2, and it’s always better to have independent well-understood simple systems instead of a tightly coupled complex conglomerate of components with unknown architecture and failure modes.

Real life might not be so accommodating, and there are at least two situations where non-stop forwarding might come handy:

- Access layer devices – provider edge routers or data center leaf switches

- Environments with very long convergence times

Access Networks

In many access networks, the customers have a single uplink to a single provider edge device. Replacing that single point of failure with two redundant devices isn’t impossible, but it quickly turns into turtles all the way down scenario.

NSF used to provide uninterrupted connectivity in non-redundant access network

In those cases you could decide to:

- Accept the reality – after all, if the end-user cannot afford two uplinks, whatever they’re doing cannot be that critical, and will survive an eventual crash of the upstream (concentration) device. Software updates are obviously a big problem.

- Throw a complex solution at the problem – buy a redundant concentration device with two CPUs and non-stop forwarding functionality. Even if the control plane crashes3, the traffic keeps flowing… or so the vendor promised in their slide deck. Just for the giggles: after throwing away so much money, the software updates are still a big problem, because nobody trusts In Service Software Updates (ISSU) to work anyway.

- Try to be as quick as possible – restart the control plane fast enough that the neighbors don’t notice (too much). Combined with ASIC-based non-stop forwarding and control-plane protocol kludges you could get pretty close to hitless upgrade.

Long Convergence Times

Imagine an edge autonomous system receiving full Internet routing from two upstream ISPs on their underpowered edge router. It takes a long time to reevaluate and change the next hop for almost a million prefixes if your vendor spent $0.02 on the CPU in the router they sold you.

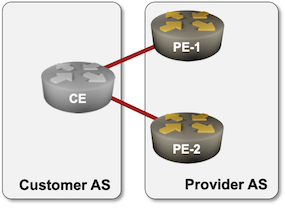

NSF used on PE-routers to work around the limitations of a CE router

In those cases it might be better to keep the routing table unchanged and hope that the hardware in the upstream provider edge router will keep forwarding packets while the software figures out how to recover from a crash. The potential outage might be shorter than the brownout caused by changing the best path for a million prefixes twice (assuming the primary upstream router crashed).

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

Let’s start with the simplest case of a device with a forwarding ASIC and single control plane (example: Arista EOS leaf switch doing Smart System Upgrade).

Control plane software restart usually triggers reinitialization of the forwarding ASIC, which will definitely stop the traffic flow until the routing protocols figure out what is where, and might also bring down the physical links, which means that the traffic keeps flowing while the control plane is dead but stops when it wakes up. Obviously a vendor implementing smart upgrade like Arista EOS takes precautions not to do that, but what happens when the software crashes?

Oh, and did I mention the control plane is dead? There’s no LACP, ARP, LLDP, STP, or routing protocols. STP is a particularly funny protocol – if the control plane stops working while the data plane is still forwarding traffic you get a forwarding loop. You can trust me on that; I’ve been there and it wasn’t pretty.

Also, there’s a reason the control plane crashed. It might be corrupted data structures, in which case one has to wonder how reliable the ASIC or linecard forwarding information is. Well, in a single-uplink scenario explained above we can choose between sending the traffic somewhere and not sending the traffic. I guess your choice depends on whether you’re a pessimist or an optimist ;)

Moving on to redundant control plane architectures. Ignoring the elephant in the room (aka: never take two chronometers to the sea), consider these minor details:

- The secondary control plane must realize the primary one is gone (byzantine failures are a never-ending source of fun).

- The secondary control plane must take over all control plane protocols and reinitialize routing protocol adjacencies (unless you’re using Non-Stop Routing, a topic for yet another blog post). At that point the adjacent nodes that were happily using the forwarding hardware in the crashed node give up – yet another instance of black hole on recovery. Of course we have a solution for this challenge: Graceful Restart (aka: the third can of worms in this wonderful voyage).

- Failover must be done extremely carefully. At no time should the forwarding hardware be reinitialized in a way that would flap the physical links or we might trigger an interface down event in the adjacent nodes. How do you implement that when trying to reinitialize a borked ASIC? I have no idea.

- The primary control plane crashed for a reason. Are you positive the secondary control plane won’t crash as well after receiving the same information from the neighboring devices?

To Recap

Non-Stop Forwarding (and Graceful Restart, and Stateful Switchover and Non-Stop Routing) are intellectually stimulating technologies that look awesome in presentations and marketing materials. They are also interestingly complex.

There might be scenarios where NSF and friends might be the best (or only) solution to a design challenge, but there’s nothing wrong with good network design using simple non-redundant components – it might work much better than a pile of vendor magic.

-

Using complex redundant systems instead of redundant architecture is never a good idea, but marketing usually eats engineering for lunch, and a large purchase order can move mountains. ↩︎

-

I’m positive a lot of people will disagree with me, particularly when their compensation depends on sales of big shiny boxes. ↩︎

-

Do I have to mention that all other things being equal, complex solutions tend to have more bugs and crash more often than simple solutions? Adding non-stop forwarding and stateful switchover to a routing stack might decrease its reliability. ↩︎

Facebook's FBOSS uses non-stop forwarding (ala the 'warm boot' feature) to manage a large fraction of their global data center. Lots of details about it in our Sigcomm paper, e.g., section 5:

https://research.fb.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FBOSS-Building-Switch-Software-at-Scale.pdf

I've just read thru the paper, and from FB's own admission, NSF/warm-boot highly complicates state management between FBOSS, routing daemons..and has resulted in a major outage -- and probably many more not mentioned -- due to complex feature interactions between warm-boot, BGP graceful restart, and the Kerberos library. Timing mismatch between these features resulted in the outage, which I'm pretty sure took them considerable pain to resolve. That's why in the very next section (7.2) that follows the mentioning of warm-boot -- which itself is used to facilitate FB's rapid deployment practice -- they mentioned the side effect of rapid deployment.

All in all, FB's experience seems to conclusively prove Ivan's overarching theme here: NSF and the rest of its voodoo result in hidden complexity that are best left untouched. Complexity, be it in feature or in topological design, or both, can result in nonlinear effects that cause major outages, as in FB's -- and plenty other -- case. And the worst thing about nonlinear effects is they cannot be modelled, and therefore, predicted. They only seem obvious in hindsight, after the fact, but at the time they happen, depending on the level of complexity, we might find ourselves scratching our heads for days. Complexity always results in fragility, and so is never a good thing. KISS.

So very dumb question but why does NSF require neighboring routers to support, but NSR does not?

Is it solely that nuance of (hopefully) not causing an interface down event in neighboring routers or is there additional complexity I might be ignorant to?

Aaaand you answered this question in Graceful Restart (GR) 101. Sorry about that!