What Exactly Happens after a Link Failure?

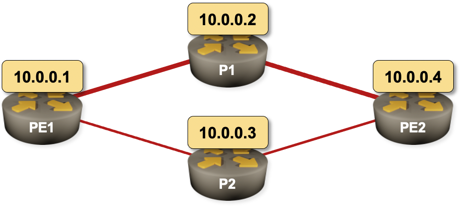

Imagine the following network running OSPF as the routing protocol. PE1–P1–PE2 is the primary path and PE1–P2–PE2 is the backup path. What happens on PE1 when the PE1–P1 link fails? What happens on PE2?

Sample 4-router network with a primary and a backup path

The second question is much easier to answer, and the answer is totally unambiguous as it only involves OSPF:

- PE1 and P1 realize they lost an interface.

- OSPF processes on PE1 and P1 are notified. They adjusts their router LSA and flood them.

- The updated LSAs arrive at PE2.

- OSPF process on PE2 runs SPF algorithm (after the SPF scheduling delay), calculates new network topology, and updates the main routing table.

- The change in the routing table is propagated to the forwarding table.

What about PE1? Here’s a high-level overview of the process:

- Interface is lost.

- OSPF process is notified about the interface loss, adjusts the router LSA, and floods it (as above)

- In parallel, SPF run is scheduled.

- SPF algorithm calculates new network topology and updates the main routing table.

- The change in routing table is propagated to the forwarding table.

Unfortunately, there’s a bit of a “then a miracle occurs” magic between steps 1 and 4. What happens with the original OSPF route pointing to now-defunct interface? Is it removed from the IP routing table? What happens with the traffic sent to the destination until the topology is adjusted?

As always, the right answer is “it depends”… this time (at least in Cisco IOS) on an obscure nerd knob.

Old School: Aggressive Purge

Until Cisco IOS release 15.x the routing table manager was the king of the hill. All routes using an interface were purged from the routing table as soon as an interface was lost, and if there was an alternate route derived from another routing protocol (or a floating static route) it was immediately installed.

Here’s a printout from the good old days1:

15:33:24.753: %LINK-3-UPDOWN: Interface GigabitEthernet2, changed state to down

15:33:24.755: is_up: GigabitEthernet2 0 state: 0 sub state: 1 line: 0

15:33:24.755: %OSPF-5-ADJCHG: Process 1, Nbr 10.0.0.2 on GigabitEthernet2 ↩

from FULL to DOWN, Neighbor Down: Interface down or detached

15:33:24.755: RT: interface GigabitEthernet2 removed from routing table

15:33:24.755: RT: delete route to 10.0.0.4 via 10.1.0.2, GigabitEthernet2

15:33:24.755: RT: no routes to 10.0.0.4, flushing

15:33:25.752: %LINEPROTO-5-UPDOWN: Line protocol on Interface ↩

GigabitEthernet2, changed state to down

15:33:25.753: is_up: GigabitEthernet2 0 state: 0 sub state: 1 line: 0

15:33:29.806: RT: updating ospf 10.0.0.4/32 (0x0) [local lbl/ctx:1048577/0x0]:

via 10.1.0.6 Gi3 0 1048578 1048577

15:33:29.806: RT: add 10.0.0.4/32 via 10.1.0.6, ospf metric [110/2001]

That behavior made perfect sense in the days when CPU frequencies were measured in megahertz, SPF was run every five seconds, and networks commonly used multiple routing protocol or floating static routes.

Unfortunately, removal of IGP routes from a failed interface also brings tons of drawbacks:

- When another protocol running on the same router monitors next hop availability, that protocol might panic and start sending unnecessary updates (example: LDP, BGP next hop monitoring)

- Even worse, when another protocol uses loss of next hop for its own fast convergence, you might get another adjacency loss even though IGP already has an alternate route in its topology database, but it just couldn’t find the time to go search for it. A prime example of this unintended consequence was aggressive IGBP fall-over.

- You might get microloops when a summary prefix or a default route points in another direction than the now-removed route. The proof is left as an exercise for the reader.

New Age: Careful and Compassionate

The drawbacks of aggressive route removal resulted in a changed policy introduced around Cisco IOS release 15.1. Under the new rules, the routing protocol owns its own routes, and removes them when it feels they should be removed.

In our scenario:

- An interface is lost

- OSPF route still points to the interface. Obviously all traffic toward the destination is dropped.

- Once OSPF recalculates the topology, it installs a modified route in the main routing table.

Here’s the printout of a new-age interface failure taken from a CSR 1000v using default SPF timers:

15:49:04.763: %LINK-3-UPDOWN: Interface GigabitEthernet2, changed state to down

15:49:04.765: is_up: GigabitEthernet2 0 state: 0 sub state: 1 line: 0

15:49:04.765: %OSPF-5-ADJCHG: Process 1, Nbr 10.0.0.2 on GigabitEthernet2 ↩

from FULL to DOWN, Neighbor Down: Interface down or detached

15:49:04.765: RT: interface GigabitEthernet2 removed from routing table

15:49:04.867: RT: updating ospf 10.0.0.4/32 (0x0) [local lbl/ctx:1048577/0x0] :

via 10.1.0.6 Gi3 0 1048578 1048577

15:49:04.867: RT: closer admin distance for 10.0.0.4, flushing 1 routes

15:49:04.867: RT: add 10.0.0.4/32 via 10.1.0.6, ospf metric [110/2001]

Throughout the whole process the IGP route remained in the routing table, IBGP sessions were not disrupted (just stalled due to packet drops), BGP next hops didn’t disappear, MPLS label assignments did not change… A perfect world, right?

It depends. You cannot do any better if you use a single IGP as the sole source of routing information… but if you use a floating static route or run another routing protocol on the backup link, the backup route won’t kick in until OSPF wakes up, realizes it has no alternate options, and removes the route from the routing table.

Modern routers have significantly lower initial SPF delays than the old gear. Here’s the default setup from a CSR 1000v:

pe1#show ip ospf | inc SPF

Initial SPF schedule delay 50 msecs

Minimum hold time between two consecutive SPFs 200 msecs

Maximum wait time between two consecutive SPFs 5000 msecs

Incremental-SPF disabled

SPF algorithm last executed 00:12:45.654 ago

SPF algorithm executed 17 times

If you really care about convergence, you could lower the initial SPF timers and the LSA origination timer down to 1 msec, and get the new routes calculated and installed in a few milliseconds… but if you really think you need that kind of performance, you just might consider a more redundant network design and fast failover technologies.

And finally, if you desperately want to have the old behavior back, configure no ip routing protocol purge interface (there’s a nerd knob for every MacGyver out there).

Other Platforms

I did my tests on a Cisco CSR 1000v. While I could have rerun the tests on a variety of different platforms, I want to share some of the fun with you.

Run the tests on your favorite platform and report the results in the comments. Here’s my testbed if you want to have a convenient starting point.

Want to Know More?

We discussed the routing protocols details in Advanced Routing Protocol Topics part of How Networks Really Work webinar.

-

Reproduced on CSR 1000v running IOS-XE 16.6.1 with initial SPF delay set to 5 seconds and no ip routing protocol purge interface configured. ↩︎