Finding End-to-End Paths: Topology and Endpoints

We know there are three main ways to move packets across a network. However, before we can start forwarding packets, someone has to populate the forwarding tables in the intermediate devices or build the sequence of nodes to traverse in source routing.

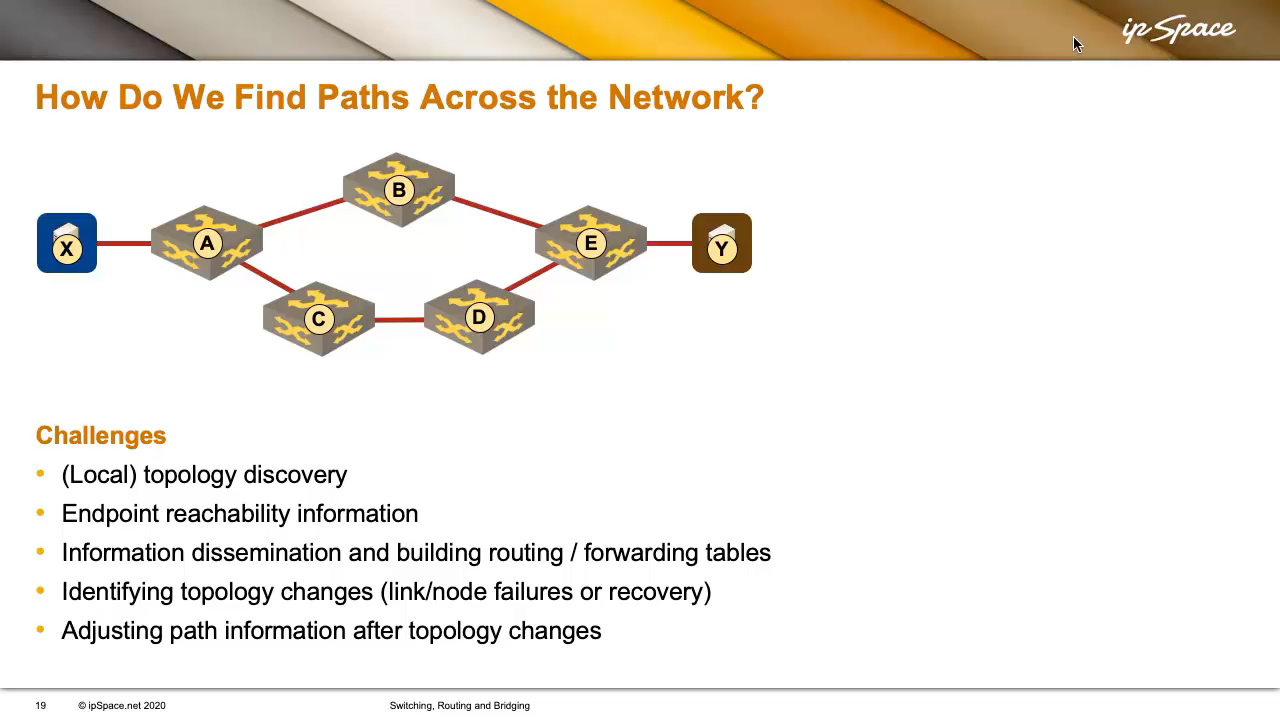

Usually, whoever is responsible for the contents of the forwarding tables must first discover the network topology. Let’s start there, using the following network diagram to illustrate the discussion.

We can argue whether it’s necessary to know the entire network topology or just the local neighborhood, and there is no correct answer. When we get to routing protocols, you’ll see that with link-state protocols, all the nodes—from A to E—maintain a complete view of the network in their databases.

On the other hand, with distance-vector protocols, a node like C would only know about its immediate neighbors, A and D. It wouldn’t even know that B or E exist. But even in that case, C still needs to know at least its local topology—it must know who its neighbors are.

After discovering the network topology, we need to determine the locations of the endpoints. Suppose we have endpoints X and Y; someone must discover that X is on the left and Y is on the right.

There are various ways to do that:

- static configuration: If A is an IP router, you’d configure a subnet on the interface connected to X.

- data plane learning used in technologies like transparent bridging. For example, the moment X sends a packet, A might say, “Oh, I’ve seen a packet from X, let me remember that.”

- In ISO CLNP, X would send End System Hellos or (as we discussed in the addressing section), allowing A to learn where X is and then inform the rest of the network.

- A might also listen to ICMPv6 Neighbor Discovery messages, ARP requests, or DHCP replies to find out the attached IPv6/IPv4 endpoints.

The process of end-to-end path discovery usually involves these steps:

- Discover some local topology.

- Identify who’s connected to whom.

- Combine and share this information with all relevant nodes.

- Build the forwarding tables.

Once the network is up and running, the paths across the network can change due to inevitable failures. For example, suppose we’ve decided that the path from X to Y is A → B → E. If the link between B and E fails (or B fails), we have a problem (if E fails, we’re out of luck no matter what).

To cope with the link- or node failures, someone needs to detect the failure, recognize that the topology has changed, determine how the change impacts forwarding decisions, and then propagate that updated information. Afterward, someone needs to adjust the path information accordingly.

For example, after the failure of the B-E link, A must learn that to reach Y, it should now go via C → D → E. There are many ways to achieve this, most of them described in the Switching, Routing, and Bridging part of the How Networks Really Work webinar.