Comparing IP and CLNP: Reaching Off-Subnet Nodes

The previous blog post in this series discussed how TCP/IP and CLNP reach adjacent nodes and build ARP/ND/ES caches. Now let’s move one step further: how do nodes running IPv4/IPv6 or CLNP discover the first-hop router that could forward their traffic to off-subnet nodes they want to communicate with?

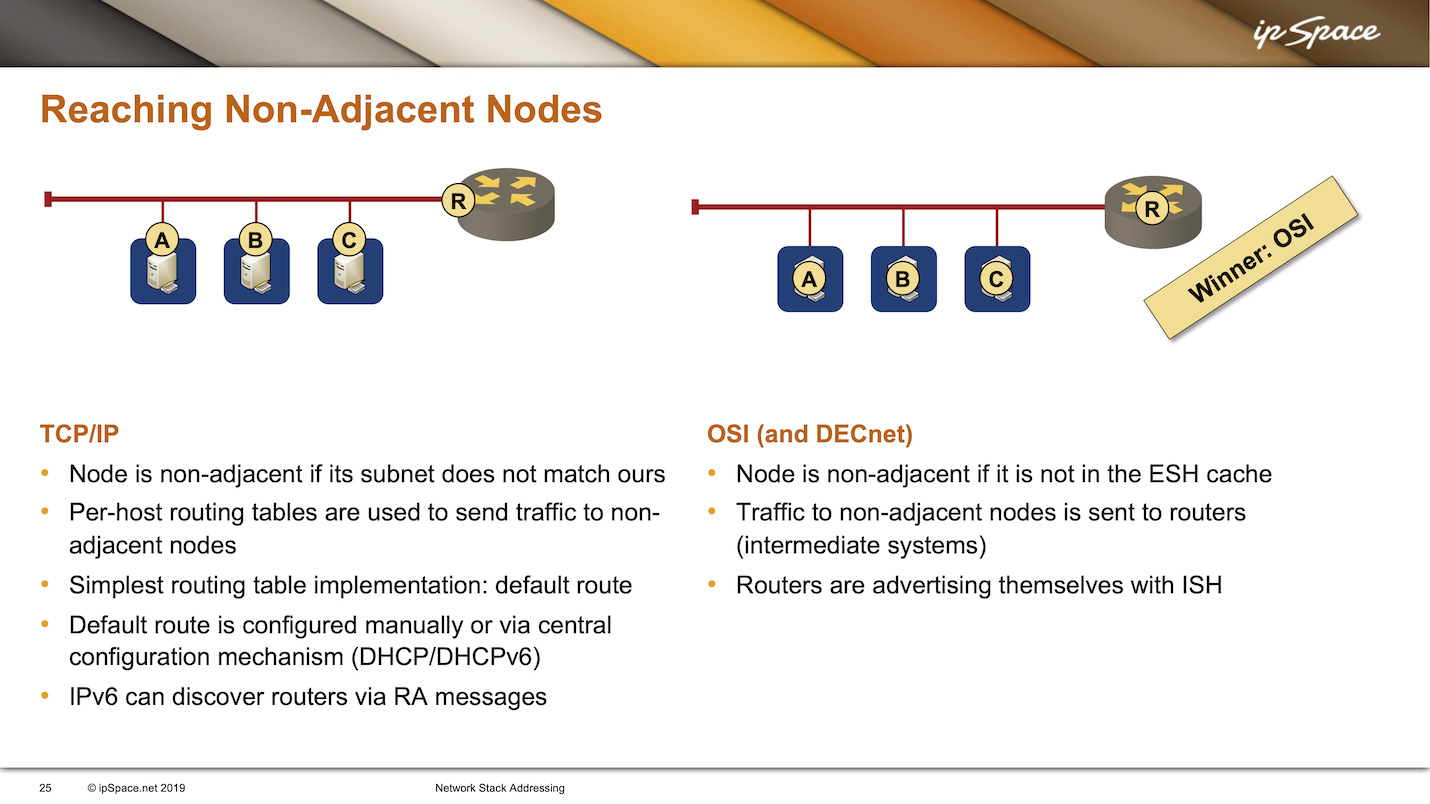

We’ve already covered how to figure out if a node is non-adjacent. In TCP/IP, a node is non-adjacent if its subnet doesn’t match ours. In OSI, a node is non-adjacent if we don’t have it in the end system hello cache.

No standard mechanism was built into IPv4 to determine who the adjacent router was. Each host in the IPv4 world has a routing table that it uses to forward packets, and one of the entries in the routing table is usually the default route – the route you use when you don’t know where to send the packets.

However, every route needs a next hop. How do you figure out the next hop for a default route? In the early IPv4 days, the answer was simple: manual configuration. Years later, when they finally implemented a centralized IPv4 configuration with DHCP, they added an option to DHCP to specify the default route. Nonetheless, the default route always had some statically configured next hop, which had to match the IPv4 address of the adjacent router.

What happens if you have two routers? We had to implement another clutch because this was not built into IPv41. Cisco Systems was the first vendor2 to realize there was a problem if we had multiple routers that had to share the same IPv4 next-hop address, and developed a proprietary protocol (HSRP) to allow routers to figure out which one of them would own the shared IP address. As a side effect, all hosts would use just one router because multiple routers couldn’t have the same IP address at the same time3 – it was impossible to implement load balancing where all routers attached to a subnet would forward some of the off-subnet traffic.

To address that, Cisco implemented GLBP, which used multiple MAC addresses for the same IP address. Alternatively, you could use the dirty trick of having two IP addresses with HSRP and routers backing each other up, but that was a nightmare because you had to tell end hosts to use two different next hops in DHCP replies.

Anyway, a few years later, we got VRRP, a standard first-hop redundancy protocol (FHRP). VRRP is now on its third version and supports IPv4 and IPv6.

CLNP (OSI networking stack) never had that problem. Routers send periodic Intermediate System Hellos (ISH), and the end hosts are always aware of all the routers connected to their subnet. If a host, based on the end system hello cache, discovered that a node was non-adjacent, it would just send the packet to the intermediate system advertised with an intermediate system hello. In the OSI world, you could have many routers attached to a LAN segment, and the host would decide which routers to use.

IPv6 copied the CLNP functionality. It has Router Advertisement (RA) messages, which are special ICMPv6 messages in which the routers say, “Hey, I’m a router (and this is the IPv6 prefix we use on this link).” After receiving RA messages from multiple routers, the hosts can decide to use one or all routers; the routers could also advertise their relative priority in the RA messages.

However, OSI and IPv6 share the same problem: when a router goes down, its RA advertisement takes a little while to time out. During this period, the host could send traffic to the disappeared router, resulting in a temporary blackout. CLNP never got a solution for that problem (everyone stopped working on the OSI stack well before path high availability became a significant issue); in the IPv6 world, we still use VRRPv3 when we want to have fast failover in case of router failures.

Finally, it would be unfair not to mention the IPv4 ICMP Router Discovery Messages specified in RFC 1256, an equivalent to IPv6 RA messages, but created years before IPv6. It was available on some routers (including Cisco IOS), but I’ve never seen it used in a production environment. Did you? Please leave a comment!

What I have seen, though, was a nasty hack. You would run RIP on the edge segments, and the hosts would listen to RIP updates4. They wouldn’t be interested in the RIP update’s contents; they would just listen to who was sending RIP messages and decide to use the source IP address of the RIP messages as the first-hop router.

-

Using two default routes with different next hops was always an option on high-end systems with full-blown TCP/IP stack, but even then, you would need some unspecified mechanism to deal with failures of adjacent routers. ↩︎

-

… that I’m aware of. If you know of an earlier FHRP implementation, please leave a comment. ↩︎

-

The first-hop anycast gateways with shared IP and MAC address became possible only when we started deploying layer-3 switches at the network edge. ↩︎

-

There was a RIP Listener component in various versions of Windows; Unix hosts and IBM mainframes usually used routed. ↩︎

I do love these posts about CLNP. They're so interesting because I know so little about OSI outside of integrated IS-IS

There is also the ICMP redirect. It should never be a comment on a routing article, but my experience shows otherwise... I once saw a network that had thousands of routes where there was a particular segment that relied on ICMP redirects rather than advertising routes across the 2 routers... meaning they were generating redirects for each IP destination crossing. They, for some reason, had huge performance issues...

Yeah, I wrote about them in the past: