Network Layer: Interface or Node Addresses

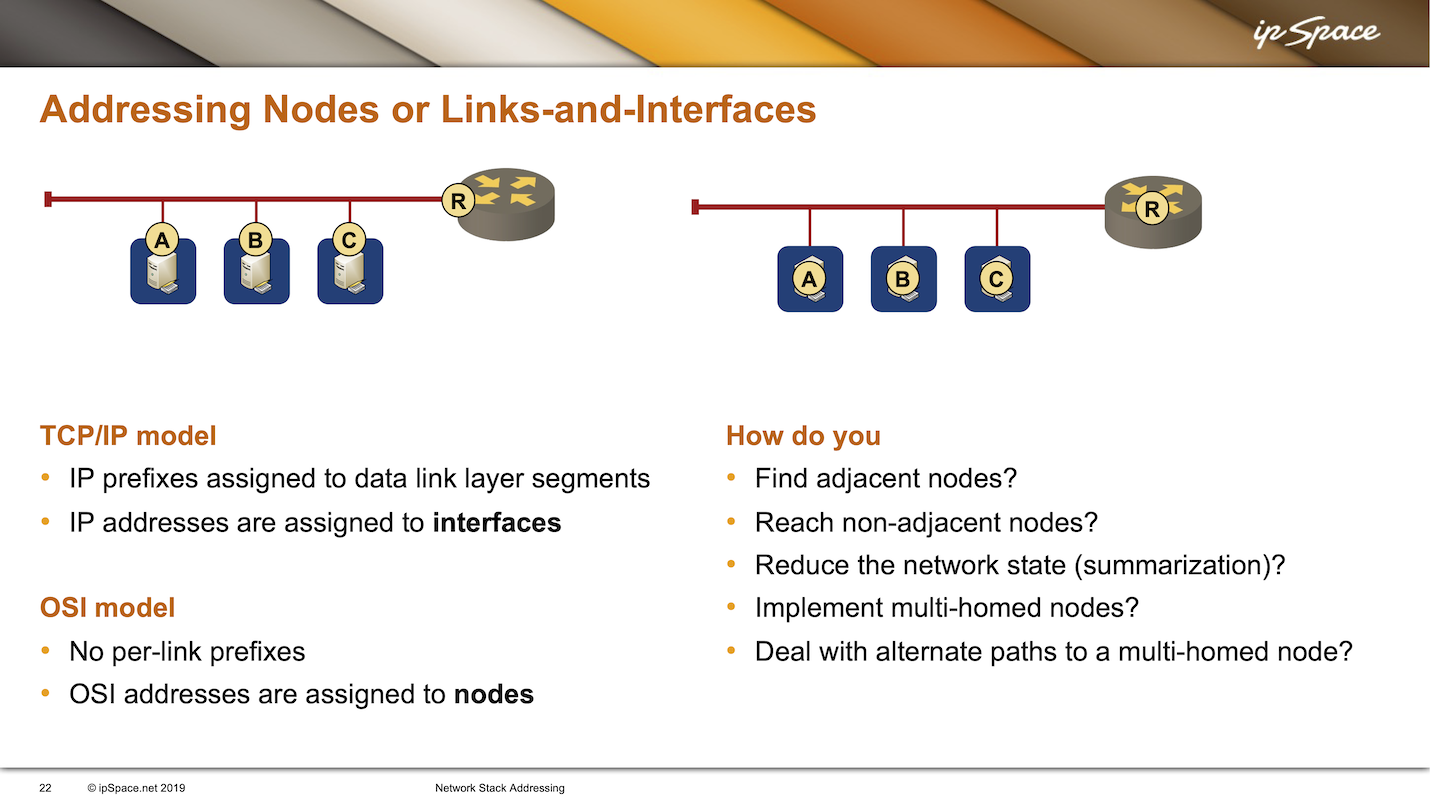

The fun question about network layer addresses is: are we addressing nodes or individual node interfaces? On the data link layer, we never had this issue because it was obvious that a data link layer endpoint is an interface, so each interface should have a unique data link layer address.

Interestingly, that’s not the case on transparent bridges. Even though they have multiple interfaces, the whole bridge has a single MAC address, so one could claim we’re addressing nodes connected to a single data link layer. The IEEE standard is unambiguous: in every relevant diagram, the MAC address sits on top of multiple interfaces because the MAC address belongs to the control plane.

The designers of IP used a similar approach: we assign IP prefixes to data link layer segments (subnets), and interfaces get IP addresses belonging to the attached subnet. For example, suppose an IP host has three network-layer interfaces. That host would have at least three different IP addresses, and those addresses would usually belong to different subnets.

The Connectionless Network Protocol (CLPN) of the had no per-link prefix. Network layer addresses were assigned to nodes. A node with multiple interfaces would have a unique MAC (or X.25) address on each interface but a single CLNP address belonging to the node1.

In the upcoming blog posts, we’ll compare the models of network-layer address assignment and figure out which one works better. As always, the correct answer is “It depends.” You’ll see that in some cases, one is better, and in some cases, the other one has an advantage, and we’ll work our way through details like:

- How do you find the adjacent nodes?

- How do you reach the non-adjacent nodes?

- How can you reduce the amount of information that has to be kept in the network?

- How can you implement multi-homed nodes?2

- How do you deal with alternate paths to multi-homed nodes?

Before going into those details, let’s figure out why these two well-known protocols ended up with two totally different addressing approaches. We’ll focus on OSI CLNP to IP and ignore the myriad networking protocols we had to deal with in the 1990s. Some assigned network addresses to nodes, others assigned them to interfaces, and there were even protocols (Novell IPX) with loopback interfaces on servers. Those protocols are long dead and irrelevant, and the old-timers (myself included) are happy to pretend we’ve never seen them.

You could argue that nobody uses OSI-based protocols anymore, and you’d be dead wrong. Every IS-IS-based network runs a protocol from the OSI protocol stack, and IS-IS routers have node-level network addresses. Regardless, we’ll use OSI CLNP as a sample implementation completely different from TCP IP to see how the choice of whether a network-layer entity is a node or an interface impacts several unexpected things.

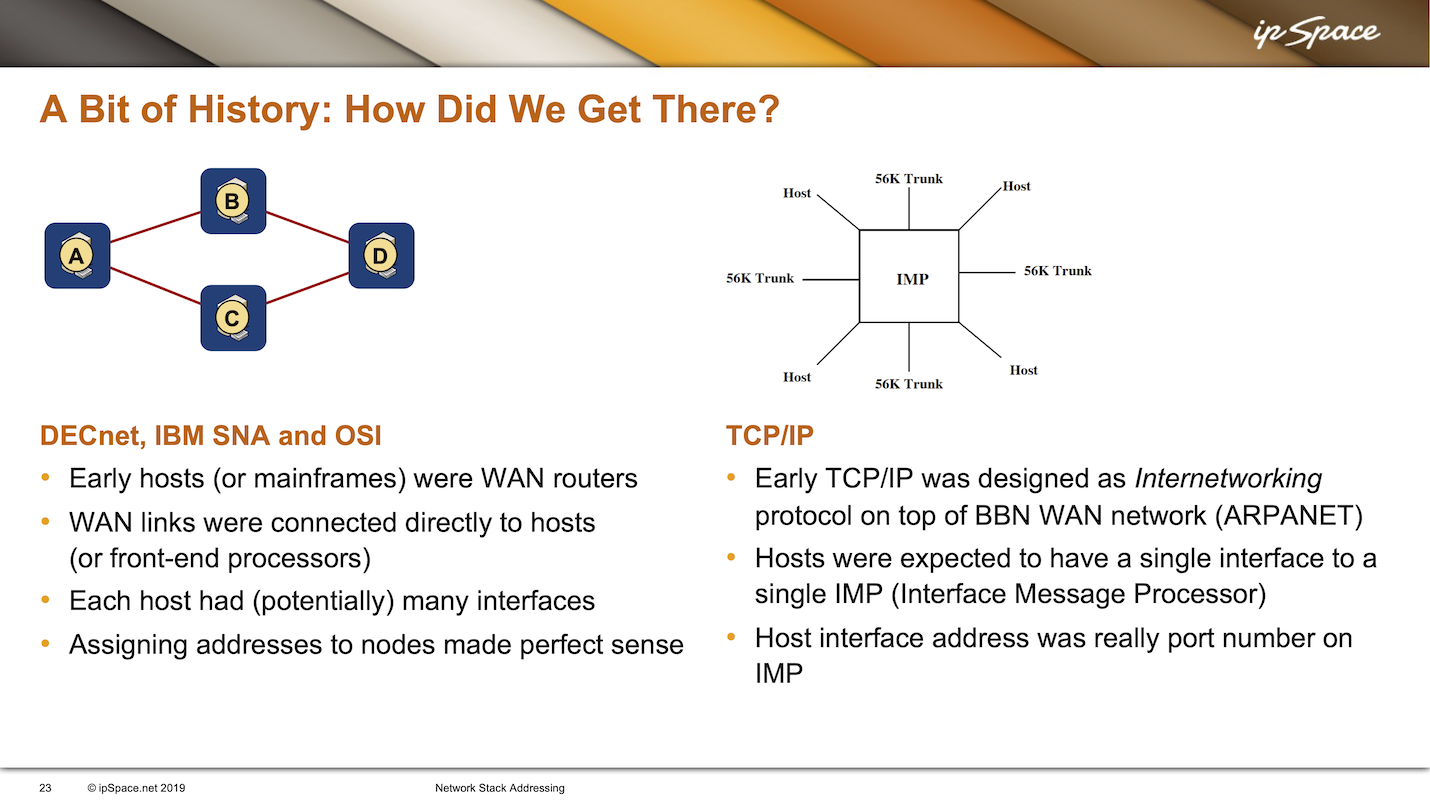

OK, it’s time for the history lesson. OSI CLNP came out of the work done at Digital Equipment Corporation. They wanted a better network-layer protocol than DECnet Phase IV, which could grow to no more than 65000 nodes while keeping the rest of the concepts intact3.

Another interesting fact: we didn’t use routers to build WAN networks in those days. Hosts with more than one interface were also routers, and it was expected to connect all sorts of links directly to PDP-11 or VAX computers4. In that world, it made no sense to address the links. Nodes were all that mattered.

IBM’s Systems Network Architecture (SNA) used a more hierarchical approach. Mainframes were the central nodes in SNA networks, but they were too expensive to waste CPU cycles. All external links were, therefore, connected to a front-end processor (FEP), and the mainframe controlled that FEP like a dedicated co-processor5. Each FEP had many interfaces, and assigning network layer addresses to interfaces made no sense from the hierarchical SNA perspective. Assigning addresses to hosts was the natural solution.

On the other hand, TCP IP was never designed as the networking protocol. As its name says, IP was designed as an internetworking protocol running on top of a network someone else built. DARPA contracted BBN to build the WAN network and provide packet transport between the attached hosts. The people running those hosts were then left to figure out how to communicate between the hosts.

The nodes in that WAN network were called IMPs (interface message processors), and each IMP would have a few trunk ports (uplinks) and a few host ports – something like a data center switch with a maximum port speed of 56 kbps. Like in Fibre Channel, the host interface address was the port number on an IMP, and every host was supposed to have just one connection to one IMP. A host connected to two IMPs would belong to two different networks, and as expected, the results of doing that weren’t exactly pretty.

A few years later, Ethernet happened, and when the IP hosts got Ethernet adapters, everyone forgot that IP was supposed to be running on top of a network-layer protocol and used IP for what it was never designed to do. The rest, as they say, is history.

Next: Finding Adjacent Nodes Continue

-

The only exception I’m aware of were the DECnet clusters. A DECnet Phase V host belonging to a cluster would have a local CLNP address and a cluster-wide anycast CLNP address. ↩︎

-

We are talking about multi-home nodes (hosts connected to two different segments), not multi-homed sites, which is a totally different problem. and finally ↩︎

-

You could say that migration from IPv4 to IPv6 mimics the migration from DECnet Phase IV to Phase V. One of them was easier to do but perished nonetheless. ↩︎

-

The link speeds were low enough that we didn’t care about burning CPU cycles for packet forwarding. ↩︎

-

What vendors call Data Processing Units (DPU) today, proving the RFC 1925 rule 11 yet again. ↩︎