Can We Trust BGP Next Hops (Part 1)?

Aldrin sent me an interesting question as a comment to one of my EVPN blog posts:

How does the network know that a VTEP is actually alive? (1) from the point of view of the control plane and (2) from the point of view of the data plane? And how do you ensure that control and data plane liveness monitoring has the same view? BFD for BGP is a possible solution for (1) but it’s not meant for 3rd party next hops, i.e. it doesn’t address (2).

Let’s stop right there (or you’ll stop reading in the next 10 milliseconds). I will also try to rephrase the question in more generic terms, hoping Aldrin won’t mind a slight detour… we’ll get back to the original question in another blog post.

If a BGP speaker R is advertising a prefix A with next hop N, how does the network know that N is actually alive and can be used to reach A?

Time to get the first elephant out of the room: this is how distance-vector protocols work. You have to trust your neighbors.

But nonetheless, even if our BGP neighbor did everything right (from the BGP protocol perspective), can we trust that the next hop it’s advertising is usable for packet forwarding? Yet again, there’s not much we can do:

- If what R is telling you is the only path to the destination, you don’t care;

- If you have multiple paths to the destination, BGP best path selection process kicks in, and while it checks whether the advertised next hop is reachable via the routing table (potentially ignoring the default route), it doesn’t consider whether the next hop is alive.

Long story short: we could never know whether the BGP next hop (VTEP in Aldrin’s question because he was talking about EVPN) is alive.

Next question: can we do better than that? TL&DR: No… at least not when using traditional routing protocols. SD-WAN with end-to-end data-plane probes is a different story.

But Routing Protocols Work

We’re usually too busy to bother with ethereal questions like this, and the routing protocols do a pretty good job to make networks work. The usual workaround is to rely on shared fate - if we have a working routing protocol session with IP address X, and that same neighbor tells us X is the next hop for Y, we blindly believe that X is alive and well, and that it’s safe to use it to reach Y. Throw BFD into the mix and you’ll know how healthy X is in a few milliseconds. Mission accomplished.

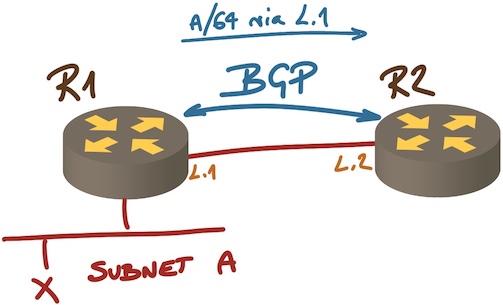

The same concept works with very simple EBGP setups like the one in the following diagram:

Next hop on an EBGP session

R1 is announcing prefix A with directly-connected next hop, and R2 can validate that the next hop is reachable, so it’s safe to assume it can use the path to reach anything within prefix A including X, right?

Wrong. Just because we got BGP traffic between R1 and R2, it doesn’t mean that R1 won’t drop traffic for A because someone misconfigured an access control list, or because there’s a software bug and the ASIC forwarding table has been misconfigured.

We also have no idea about the forwarding performance of R1. Maybe traffic toward prefix A is software-switched and it would be better to use an alternate path that might have higher cost (due to lower-speed links) but better forwarding performance. We simply don’t know. No routing protocol would give you that information (for a very good reason: scalability and stability).

From EBGP to IBGP

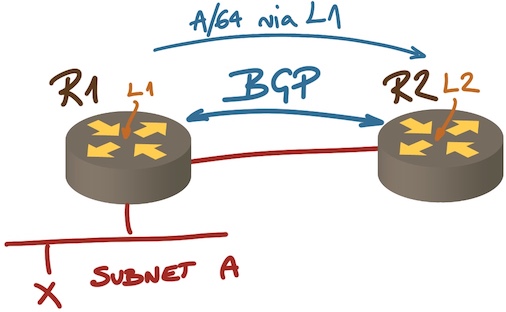

How about a simple IBGP setup like this one:

Next hop on an IBGP session

In this setup an IBGP session is established between loopback interfaces R1 and R2. R1 is advertising L1 (its loopback address) as the next hop to reach A… but nobody ever uses L1 to forward packets to A. Considering the liveliness of L1 is as useful as pondering the number of angels that can dance on a pin.

What really happens is that R2 uses recursive routing table lookup to find next hop to reach L1, and then hopes that if the next hop to L1 is reachable (for example, it’s advertised by OSPF), it’s safe to use it for any destinations with L1 as the next hop.

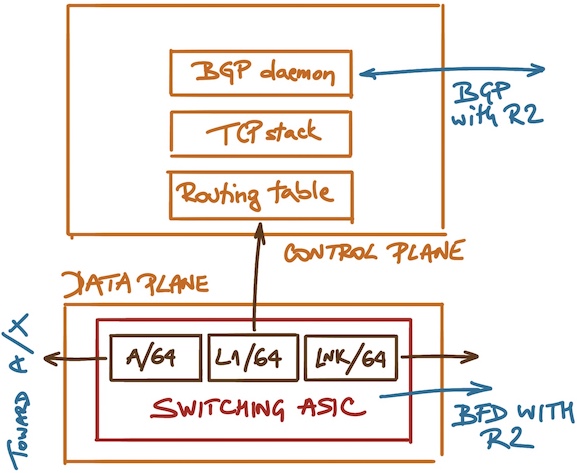

You might say “gee, that makes perfect sense” (ignoring for the moment the ACL SNAFU I mentioned above), but consider how packet forwarding within R1 is really implemented:

Control and data plane in a router running BGP

You might be running BFD between R1 and R2. That tests the rightmost forwarding entry in the switching ASIC.

IBGP session between L1 and L2 is up and running, or at least you got the last packet from L1 less than three minutes ago1. The only thing that tells you is that the switching ASIC is punting packets for L1 to the CPU, that the operating system running on R1 didn’t mess up its routing tables, that the TCP stack hasn’t crashed, and that the BGP daemon on R1 is healthy. Does it tell you anything about forwarding path toward A? Is the forwarding entry for A valid? Does R1 have transceiver failure on that interface? We have no idea.

Conclusion: Even if you do everything right, you can never be sure that traffic sent toward a BGP next hop will reach the advertised destination. You might as well stop bothering and get a life, networks usually work reasonably well.

So far we covered the two simplest scenarios. The next installment of this saga describes networks with more than two routers.

You might also want to watch How Networks Really Work webinar (parts of it are available with free ipSpace.net subscription) or explore other BGP resources we’ve created in the last decade and a half.

Next: Next-Hop and VTEP Reachability in EVPN Networks Continue

-

The default BGP session timeout ↩︎

Addressing the problem of BGP Next Hop reachability, I'm not familiar in the particular case of EVPN, but the Cisco implementation of BGP has 2 features enabled by default which are meant to address this issue specifically, the BGP Scanner process and (the even faster) Next Hop Tracking.

And that's just for indirect / 3rd party next hop. If your BGP peering (regardless of whether it is iBGP or eBGP, even though the latter is the recommended best practice), then fast externall fallover will immediately kill the neighbor and flush all routes which it learned from that neighbor.

Of course, none of these features will protect you against gray SW/HW failures, such as faulty line card which still appears as UP but is not actually forwarding any traffic.

@Ciprian: You're absolutely right, but those are control-plane optimizations that either detect BGP session failure faster than you'd be able to do it with BGP timers (in case BFD is not available), or flush invalid routes from BGP table faster than what we had in the past with periodic BGP scanner.

Neither of these optimizations address the challenge described in this blog post: can we trust that a next hop advertised by BGP is usable for traffic forwarding.