Disasters and Recoveries, Part 2

You wouldn’t believe what your second most pressing problem is when you lose electricity for a few days in the middle of a winter storm: freezer. Being a good engineer focused on redundant solutions, I bought a diesel generator before moving into the hills to keep the freezer at a reasonably low temperature in case of a long-term power loss.

I also thought about using the same generator to run our central heating. As always, I found a huge disconnect between theory and practice.

Lesson#1: Untested recovery solutions are useless. Relying on them is stupid.

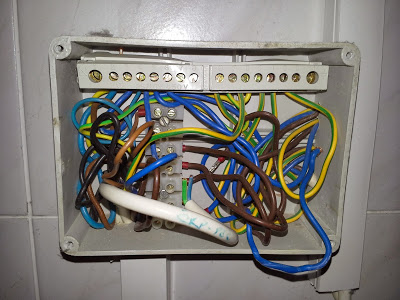

During the first longer power outage we experienced last Friday I decided to connect the central heating to the generator. Opening the distribution box revealed a huge spaghetti mess of unlabeled cables.

Lesson#2: Documentation is mandatory in a well-run IT operation, but it’s crucial during any disaster recovery process. You have to have a well-documented current state and the step-by-step recovery procedure.

I’d explained my generator-run-central-heating idea to my electrician when he’d been installing the wiring, but obviously he never understood me and did things his way (hint: totally useless for my purposes).

Lesson#3: Badly implemented redundant design is sometimes worse than a non-redundant one. With a non-redundant design you’re at least aware of the actual (non)capabilities of the system.

Even worse, the electrician decided to make his life easier and didn’t use proper wiring techniques – some cables running from the central heating to the distribution box had a single wire connected to the patch panel (the other two were simply cut off).

Lesson#4: Don’t trust subcontractors without verifying their work at least a few times, or you might be in for a nasty surprise at the worst possible time.

Eventually I gave up – there was simply no way to untangle the mess, and get the central heating controller connected to the diesel generator without a potential catastrophic error. I decided it was more important to have a working unit after the power would be restored.

Lesson#5: Know when to give up. Implementing untested ideas under time pressure might be worse in the long run than not doing anything.

Learn From Your Mistakes

After the heating season is over, I’ll definitely rewire the whole thing in a way that will make it easy to disconnect the heating unit from the power grid and plug it into a generator.

Lesson#6: Every good engineer should learn from his own errors, omissions and plain stupidity. The lesson might have been expensive, but if you don’t improve your design, implementation or procedures based on what went wrong you just wasted a huge opportunity.

I’ll also buy a small camping gas stove … did I mention that we replaced a gas stove with a great new induction stove a few years back and never though about redundancy?

Lesson#7: Don’t forget to update your disaster recovery design and procedures every time you introduce new technologies/products or replace an existing one.

We experienced same problems here 15 years ago:

http://archives.radio-canada.ca/environnement/catastrophes_naturelles/dossiers/265/

and lots of power-lines have been routed underground since then. Pylones have also been redesigned:

http://www.quebecurbain.qc.ca/archives/jc100_0095b.jpg

Stay warm

On a more serious front, you get way more bang for the buck if you manage to get the central heating up and running.

No, i'm not a DIY maniac. I do hire people when i have to. But when I need a "life support system" i do it myself, even if it takes a long time to get educated and to implement. This approach has not failed me so far and yes, I do lose power from time to time, sometimes for a week or more.