Azure Route Server: Behind the Scenes

Last week I described the challenges Azure Route Server is supposed to solve. Now let’s dive deeper into how it’s implemented and what those implementation details mean for your design.

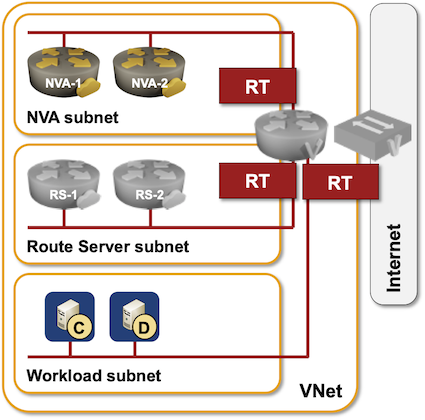

The whole thing looks relatively simple:

- Azure Route Server needs a dedicated subnet within your VNet.

- Two control-plane VM instances are created when you create a Route Server instance. Their IP addresses are usually the third and fourth IP addresses within the dedicated subnet (you can get them with az network routeserver show command).

- When you configure BGP peering with the Route Server, you can establish multihop EBGP sessions between your Networking Virtual Appliances (NVA) and the two route server control-plane instances and send them external routes.

- The route server control-plane instances will send your BGP routers VNet prefix(es) and prefixes from all peered VNets.

The details are a bit more interesting:

- There’s another router in the middle (Azure virtual router) that you can’t interact with;

- Your NVA VM is really a router-on-a-stick;

- The Azure virtual router controls packet forwarding to- and from your NVA.

- The route server VMs are therefore pure control plane instances. While they advertise IP prefixes with their IP address as the next hop, the actual packet forwarding is done by the interim virtual router.

Now pause for a moment and think about the implications. Does it already look like CCIE Lab from Hell scenario?

Let’s start with how will your routers reach Route Server instances? Your NVA instance probably has a default route to reach the Internet, and that default route will be used to send BGP traffic to the route server instances (in a different subnet). Once the BGP session is up, the route server instances advertise VNet prefix. That prefix is more specific than the default route, so you get into a recursive routing situation where a BGP next-hop is reachable over a prefix advertised by that same BGP next hop. Kaboom… or not, depending on the NVA routing stack implementation (interestingly, Quagga bgpd had no problem with that).

Lesson learned: you better have a static route for the route server subnet pointing to the Azure virtual router (first IP address in NVA subnet).

Now imagine that you plan to use the NVA instances to inspect all traffic entering and exiting the virtual network. No problem, just advertise the default route from the NVA instances, and route server will take care of the details, right? Wrong. Kaboom.

The moment your NVA advertises a default route to the Azure route server, that default route gets installed into the routing table(s) of Azure virtual router, and is also used for all traffic sent by NVA instances. In other words: all traffic sent toward unknown destination by your NVA virtual machines will be dutifully routed back to those virtual machines. We have a winner… and you probably also lost external connectivity to your VNet as a result of that forwarding loop, so you can’t even fix the problem without shutting down the NVA instances or deleting route server peering. Isn’t it great to have an out-of-band orchestration system, so you don’t have to drive to an Azure region to power-cycle your VMs?

To fix that problem, use a separate route table for the NVA subnet with a user-defined default route pointing to Internet next hop. User-defined routes1 take precedence over virtual hub routes2, and so the route server cannot overwrite the default route used within the NVA subnet.

After considering all this, please tell the next person who has an opinion that we don’t need networking engineers to deploy complex designs in a public cloud that he’s shouting from the highest peak of Mount Stupid.

Next time: hands-on route server experience (including waiting for an eternity while it’s being provisioned).

More Details

Did parts of the above sound like Latin? You’ll find the necessary details in Microsoft Azure Networking webinar, which already includes Azure Route Server video.

You could also use my test setup to take Azure route server for a spin.

Excellent explanation Ivan, I listened to the videos a few times and then found these blog posts which further cemented the concepts. If anything after reading this, it only solidifies in my mind the even greater need for experienced network engineers when dealing with networking in public cloud.